The Ghosts of Shanghai

A vibrant Jewish community appeared on the banks of the Huangpu River in old Shanghai, for a brief flash in history. Now scholars and former refugees of this amazing enclave are trying to make sense of it all

By Ron Gluckman/Shanghai

Go to a list of famous Shanghai Jews

Y

U WEIDONG BRINGS HIS bicycle to a stop alongside a corner dress shop. On the wall behind three mannequins is a tiny brass plaque. Puffing with excitement, Yu recites the inscription, a memorial to his favorite Shanghai ghosts. Three weeks later, on the other side of the world, Judith Moranz rests her head upon her husband Karl's shoulder. Time peels away in Las Vegas' MGM Grand Hotel ballroom as they sway to big band tunes, soundtracks of their youth. Her eyes grow misty. The songs are sentimental favorites from wartime America, but they take Moranz back to that same street corner in Shanghai.Moranz was 8 when she left Shanghai in 1949, decades before Yu was born. They have never met, but are linked in an odd way. Yu has spent his life studying people like the Moranzes and the couples dancing around them. In Vegas, they look like average tourists. Yu, though, sees them as holy spirits of a rich and mysterious age.

A half century ago, they inhabited an intriguing corner of China: Shanghai's boisterous

Jewish ghetto. Viennese gentlemen sipped coffee outside Austrian bakeries so authentic

that the neighborhood was called Little Vienna. Nearby were kosher butcher shops and

German delicatessens. Diners read Shanghai papers printed in German, Polish, even Yiddish.

Candles for Jewish holidays were sold nearby at Abraham's Dry Goods, and the tango was

danced nightly at Max Sperber's Silk Hat.

A half century ago, they inhabited an intriguing corner of China: Shanghai's boisterous

Jewish ghetto. Viennese gentlemen sipped coffee outside Austrian bakeries so authentic

that the neighborhood was called Little Vienna. Nearby were kosher butcher shops and

German delicatessens. Diners read Shanghai papers printed in German, Polish, even Yiddish.

Candles for Jewish holidays were sold nearby at Abraham's Dry Goods, and the tango was

danced nightly at Max Sperber's Silk Hat.

A unique Jewish community once thrived in Shanghai, where Jews had worked since the opening of China's largest treaty port in 1842. A century later, European Jews fleeing Adolf Hitler poured into Shanghai where, even among the large international settlements, they stood out, a distinct community with its own hospitals, theaters, schools and sports leagues. Life wasn't always jolly, of course. Jewish refugees were later herded into Hongkou ghetto in the city's northeast, where food was scarce and disease rampant. But in Shanghai, unlike much of the world, nearly all the Jews survived the war.

Shanghai's role as savior of these souls is the stuff of classic cinema -- indeed, many books and films are being produced to tell a tale that makes Schindler's List pale in comparison. Before and during World War II, some of Shanghai's richest men conspired to save tens of thousands of Jews. Exactly how many is not known, but some historians say Shanghai saved more Jews from the Nazi Holocaust than all Commonwealth countries combined. Among them were hundreds of religious scholars. A wartime chaplain in Shanghai wrote that 500 scholars in Shanghai maintained the nearly 6,000-year tradition of Jewish teaching, making it at that time one of the world's great Jewish cities.

Ironically, this remarkable religious community vanished even more rapidly than it took root. When civil war enveloped China, the refugees fled again. By the end of the 1950s, Shanghai's synagogues were shuttered and its Jews gone.

And that should have been the end to this little-known tale. But, in another twist to the saga, about a decade ago Jewish culture returned to China, where religion has been suppressed for half a century. Stories from the Talmud are being retold and Hebrew scriptures studied again. Most remarkable of all, Shanghai's new Jewish scholars are all Chinese.

Yu is one of them. He is a graduate of China's first Jewish-studies program, which was

pioneering in every way. Students used old Hebrew newspapers and concocted lessons

themselves when no Jewish teachers could be found. Five other students joined the pilot

program of Jewish and Hebrew studies launched by Peking University in the mid-1980s. The

other students later went abroad, to Israel or the U.S., leaving Yu with an odd

distinction: he's probably the sole Hebrew-speaking college graduate in a country of 1.2

billion people.

Yu is one of them. He is a graduate of China's first Jewish-studies program, which was

pioneering in every way. Students used old Hebrew newspapers and concocted lessons

themselves when no Jewish teachers could be found. Five other students joined the pilot

program of Jewish and Hebrew studies launched by Peking University in the mid-1980s. The

other students later went abroad, to Israel or the U.S., leaving Yu with an odd

distinction: he's probably the sole Hebrew-speaking college graduate in a country of 1.2

billion people.

For years that distinction was meaningless. Yu found some work as a tour guide for a trickle of curious American Jews seeking what signs remained of the Jewish community in Shanghai. Yu also practiced Hebrew with visitors from Israel. But, up until a few years ago, they were even rarer. China and Israel, two ancient nations reborn after World War II, lacked ties until 1992.

Since then, there has been a steady increase in exchanges between sinologists studying Shanghai's Jewish community, and the local academics who are trying to make sense of the odd little Jewish settlement that flourished in their midst. "We have to rescue this history," insists Xu Buzeng, 70-year-old doyen of Jewish scholars in Shanghai, who realized a lifelong dream last fall when he visited Israel on a fellowship to Hebrew University. "We must research and write about this rich period of our history," he says. "Otherwise, in 10 to 20 years, when we are gone, this history will be lost forever."

Also desperate to salvage Shanghai's Jewish heritage are thousands of survivors of the wartime refuge. They have been meeting with greater urgency in the last few years. In Las Vegas last September, nearly 400 attended one gathering, the fourth and largest ever Old China Hands Reunion. Tables were piled with books, mostly self-published memoirs. Betty Grebenschikoff said she wrote Once My Name Was Sara for her children and grandchildren, "so they would know what happened. The Shanghai experience was amazing, and few in the world know about it." Added Evelyn Pike, author of Ghetto Shanghai: "I tell people to write. These stories ought to be told."

Jewish history in China dates to at least the 8th century, when West Asian traders roamed the Silk Road. A Jewish settlement was established in the city of Kaifeng, in what is now Henan province, where a synagogue was built in 1163 and thousands of Jews worshiped openly. Kaifeng today boasts some Hebrew writing on tombstones, but no living link to its Jewish past (although some residents claim Jewish blood). By the 20th century, the community in Kaifeng was eclipsed by cities like Harbin, Ningbo and Tianjin, which all had sizable Jewish settlements.

None rivaled Shanghai. Herman Dicker's Wanderers and Settlers in the Far East details three distinct periods of Jewish immigration to Shanghai. The first began in the 1800s, with the arrival of Jewish businessmen from West Asia, mainly Baghdad. Among them were the Sassoons and Kadoories, the latter one of Hong Kong's wealthiest families. They financed some of Shanghai's finest colonial architecture, including the magnificent Children's Palace (formerly the Kadoorie estate, Marble Hall), the art deco Peace Hotel (then the Cathay Hotel) and Shanghai Mansions, a Sassoon building that was used to process, and illegally house at times, hundreds of refugees. In 1932, the Shanghai Stock Exchange listed almost 100 members; nearly 40% were Sephardic Jews. They joined the city's finest clubs, a privilege denied Jews even in liberal parts of Europe and America. As a measure of their security in Shanghai, flamboyant Victor Sassoon reportedly boasted, "There is only one race greater than the Jews, and that is the Derby."

This small Jewish circle was affected in the early 1900s by a second wave of immigration that brought Russian Jews fleeing the pogroms (campaigns of repression) and, later, the Russian Revolution. Most settled in northern China. By 1910, Harbin had 1,500 Jews, but the number grew to 13,000 by 1929. Many moved south to Shanghai after the Japanese took Manchuria in the early 1930s.

The Russians did not mix much with Shanghai's Jewish elite. Russian Jews ran their own stores and restaurants, read Russian newspapers and enjoyed their own music and theater. Many settled in the French quarter, where they founded the Jewish Music Club. There were conflicts, especially over religious issues, but the Jews were no different than Shanghai's tens of thousands of other foreigners, whether British, American, French, German or Japanese. All kept to classes defined by ethnic and economic lines. Otherwise, rules were few in Shanghai, and opportunities endless.

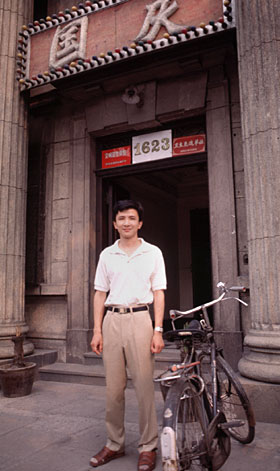

"We lived our lives with great panache," says Shanghai-born Mario

Machado (pictured left in front of a bulletin board where old friends post

messages to and mementos of long-lost Shanghai pals) a

longtime Hollywood broadcaster who organized last year's Old China Hands conference.

"Shanghai was magical. We were a proud group of people, a diverse group, bound by a

special camaraderie."

"We lived our lives with great panache," says Shanghai-born Mario

Machado (pictured left in front of a bulletin board where old friends post

messages to and mementos of long-lost Shanghai pals) a

longtime Hollywood broadcaster who organized last year's Old China Hands conference.

"Shanghai was magical. We were a proud group of people, a diverse group, bound by a

special camaraderie."

The community was self-contained. There were seven synagogues, four cemeteries and a club where performances were given by some of Europe's finest musicians. Children attended a Jewish school financed by Horace Kadoorie.

They joined Jewish scout troops, competed in Jewish football leagues and chess tournaments. Those with pocket money could ride one of 2,000 rickshaws -- Asia's largest fleet -- owned by A. Cohen. The building that housed his Star Garage still stands on Nanjing Road. And they cheered as Jewish boxers like Sam Lefko, Kid Ruckenstein and Laco Kohn pounded their opponents.

Why Shanghai? As the rest of the world closed to desperate Jews seeking escape from the Nazis, Shanghai remained one of the rare free transit ports. Explains The Muses Flee Hitler, a book by Washington's Smithsonian Institute released to honor the centennial of the birth of Albert Einstein (who visited Shanghai twice in the 1920s): "Shanghai required neither visas nor police certificates. It did not ask for affidavits of health, nor proof of financial independence. There were no quotas."

Thus began the third phase of Jewish migration; an estimated 20,000 poured into

Shanghai from 1937 to 1939. Some merely passed through, en route to the Americas,

Palestine or Australia, but about 90% stayed. Restrictions were put on immigration in

August 1939, but still they came in droves as war consumed Europe and other avenues of

escape closed. Thousands arrived in rags, with neither entry permits nor any means of

support. Housing for latecomers was extremely sparse -- hundreds languished in temporary

shelters. The four-person family of Ralph Hirsch, who escaped from Berlin to Shanghai as a

boy in 1940, had a tiny apartment for six months, then lived in one small room for six

years. Other refugees recall sharing one room with several families.

Thus began the third phase of Jewish migration; an estimated 20,000 poured into

Shanghai from 1937 to 1939. Some merely passed through, en route to the Americas,

Palestine or Australia, but about 90% stayed. Restrictions were put on immigration in

August 1939, but still they came in droves as war consumed Europe and other avenues of

escape closed. Thousands arrived in rags, with neither entry permits nor any means of

support. Housing for latecomers was extremely sparse -- hundreds languished in temporary

shelters. The four-person family of Ralph Hirsch, who escaped from Berlin to Shanghai as a

boy in 1940, had a tiny apartment for six months, then lived in one small room for six

years. Other refugees recall sharing one room with several families.

It was a constant struggle, but the community took care of itself until Pearl Harbor in 1941. Foreigners from Allied nations were sent to prison camps. German and Austrian Jews, the largest group, were considered stateless refugees, and were confined to Hongkou ghetto in 1943. "There was no barbed wire and it wasn't heavily patrolled, but adults needed passes to go out," says Hirsch, American director of a group called the Council on the Jewish Experience in Shanghai. Yet, with all its deprivations, Hongkou was like summer camp compared with ghettos in Europe, where Jews were penned in by the Nazis, who eventually sent most to their deaths.

In Shanghai, the Jewish community quickly rebuilt itself after the war, but the city would never be the same. The Japanese were defeated, yet fighting continued in the civil war between the Nationalists and Communists. An exodus of foreigners began immediately. Options were puzzling. Zoya Shlakis fled Lithuania to escape the Nazis, only to find his nation occupied by the Soviets after the war. "I was considered a Russian immigrant," he says, "but I wanted nothing to do with the Communists." Shlakis went to Taiwan and later emigrated to the U.S., "where I was termed a Chinese immigrant!"

Some Shanghai-born Jews were sent to third countries. Israel evacuated several ships of Jews from Shanghai as Mao Zedong's Red Army crept closer in 1948. Several towns in Israel were settled entirely by Shanghai survivors. The U.S. was the most desired destination; San Francisco has a synagogue founded by, and whose congregation is still largely made up of, former Shanghai residents.

Karl and Judy Moranz left in 1949 for Italy on the same boat. "We were from Vienna. We lived three blocks apart," Karl says. Yet they didn't meet until a decade later in New York, at a 10th-anniversary ball for Shanghai survivors. She was 17, he nearly 30. "I bought her a drink and she gave me her number." A year later, they were married. Not all stories ended happily. By 1953, 440 Jews remained in Shanghai, and the number fell to 84 by 1958. Most were sick or elderly, and in the care of the Council of the Jewish Community of Shanghai, which ran a shelter until 1959.

Afterward, virtually all trace of Jewish life in Shanghai was wiped away. Schools and shops closed, and most synagogues were demolished by China's new rulers. Shanghai remained unobservant of its Jewish legacy for three decades. Then, one by one, the spirits began stirring. I felt their presence during my first visit to the city in 1990. And little wonder, since I was staying at the old Jewish Music Club, now the Shanghai Music Conservatory. A foreign student mentioned some old professors who had formed a Jewish study association. After numerous calls, I finally tracked them down.

In a dingy basement, I found a dozen mostly retired teachers arguing odd points from the Bible. Odd, because it was apparent few, if any, had ever read a Bible. They had half a dozen associations, with ambitious names like the Center of Israel and Jewish Studies of the Chinese Institute For Peace and Development Studies. But all involved the same men, exchanging the same second-hand scholarly gossip. Genuine information was rare, and for good reason: Such study was not sanctioned by the government.

"We've produced more than two dozen papers to date," one retired professor told me. When I asked for copies, he sheepishly admitted: "None of them has been published. We don't have permission." Some were thrilled to actually be meeting a Jew, and one with a Chinese connection -- my father and his parents also escaped from Germany through China, but not by way of Shanghai.

Still, many were genuine scholars, with a keen interest in sharing information. I found this out after a meeting with one of the men. We sipped tea for hours, discussing practically anything but our common interest. Then at the door, the professor paused to casually mention a report from the city archives, barred to foreigners. Holding excitement in check, I said farewell. Just before the door closed, though, he pulled some papers from under his shirt and handed me the report. It sounds funny now, but China was a nervous place at the time.

Since then, I have kept in touch with these scholars, watching with fascination as their field slowly gained credibility. As it did, so too did their lives improve. By my next visit, they had moved from their basement office to a large estate. On the doorway was a smart brass nameplate. And, best of all, the professors proudly showed me their first book, a collection of essays on Jewish subjects, written in Chinese.

By then, the various associations had blended into the Center of Jewish Studies, headed by Pan Guang. A young history professor from the Shanghai Academy of Social Service, Pan is the official spokesman on this subject, and it is a sign of the times that he travels much of the year, a feted guest at Jewish conferences eager to have a Chinese speaker on board. Pan recently published The Jews of Shanghai, the first book about the community in English and Chinese.

Nor have the other academics been passed over. Xu Buzeng, who translated into Chinese David Kranzler's definitive 1976 work, Japanese, Nazis and Jews: The Jewish Refugee Community of Shanghai, 1938-1945, has also lived to see published several of his papers on prominent refugee musicians and composers. Xu Xin, perhaps China's leading Judaic scholar, heads a Jewish-studies program in Nanjing. He recently coordinated the release of an abridged Chinese version of the Encyclopedia Judaica, a 900-page volume that took three years and the work of 40 scholars to complete. And Yu tutors Shanghai residents in Hebrew. "People are interested in Jews," he says. "Everyone has heard about them and how they are good with money."

China and Israel have only had diplomatic relations for five years. Politics kept them in separate spheres, even though Israel was among the first nations to recognize Communist China. "There's a lot of curiosity," says former Consul General Moshe Ram, who has been regularly reminded of the wartime Jewish community since opening the Israel mission in Shanghai in 1994. "But let's put things in perspective. It's a good story. In fact, it's a great story. But it's small, and the impact is minimal." He tries to focus on the present, particularly on increasing trade between Israel and China.

"The Jews and China were always good friends," notes Pan Guang. Indeed, China was an early supporter of the concept of a Jewish state, according to Reno Krasno, a Shanghai refugee and author. In a paper published by the 12-year-old Sino-Judaic Institute in California, Krasno reprints a letter of support from a founder of modern China, Sun Yat-sen. China was among members of the League of Nations that in 1922 voted in favor of the Palestine Mandate, proposing a Jewish homeland.

All this history wells up in Shanghai, where a determined researcher can still find Stars of David decorating old tenements in the French quarter. And interest is being rekindled by a growing number of Jewish businessman, who hold regular religious services in the city.

"There's a real cultural connection between the Chinese and the

Jews," Pan says. "Many people write about this. The Chinese have been called the

Jews of Asia, you know. Both emphasize family and education. And both build cultures, the

oldest in the world. Both peoples also live in many places, but the people never

change."

"There's a real cultural connection between the Chinese and the

Jews," Pan says. "Many people write about this. The Chinese have been called the

Jews of Asia, you know. Both emphasize family and education. And both build cultures, the

oldest in the world. Both peoples also live in many places, but the people never

change."

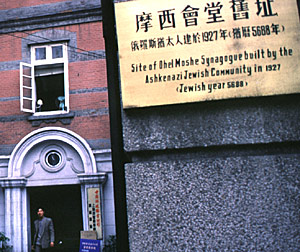

Last year, Shanghai opened its first Jewish museum, inside the old Ohel Moishe temple. There is no real collection, only a few framed photos of refugees and some of the prominent Jews who have visited. But outside, the narrow streets of Hongkou are as alive as ever.

In 1994, Hirsch returned to the city with a few former refugees. It was an odd step forward in Chinese-Jewish relations. The officially sponsored visit failed to take in many of the old Jewish sites, but did include a tour of Pudong and a pitch for investment.

Still, most were smiling: Shanghai's ghosts had come home. "Hardly anything has changed," Hirsch said, "least of all the people. It's cleaner now, but Shanghai looks the same, it sounds the same, and it smells the same."

FAMOUS SONS

Among the Jewish community of Shanghai were many who made a mark on China, the region or the world. Among the famous sons and daughters of Shanghai were:

The Kadoories - This family made its fortune in Shanghai and Hong Kong real estate and utilities; their Hong Kong and Shanghai Hotel chain (including the Peninsula) is among the finest in the world.

The Sassoons - One-time opium traders who went big-time into trading and property.

Morris Cohen - Known by his nickname Two-Gun Cohen, he served as bodyguard and aide-de-camp to Sun Yat-sen, eventually becoming a Chinese general.

Dr. Jakob Rosenfeld - An Austrian who spent nine years overseeing health care for the Communist army.

Michael Medavoy - Lived in Shanghai until age 7, he went onto a career as Hollywood mogul at Columbia, Orion and TriStar Pictures.

Peter Max - Influential American pop artist was born in Germany, but spent 10 years in Shanghai.

Mike Blumenthal - Became U.S. Treasury Secretary.

Eric Halpern - With other Shanghai Jews, he founded the Far Eastern Economic Review, and was its first editor.

Ron Gluckman is a reporter from San Francisco, the "Shanghai of the West," who first came to China while retracing the route of escape from Hitler taken by his own Jewish father and grandparents. They left Nazi Germany in Sept 1940 and traveled by train through Eastern Europe, across Russia and via China to Korea, Japan, then boat across the Pacific. He spent six years, on and off, researching this story, which ran in Asiaweek in June 1997.

For a related story, please click upon Old China Hands. Recently, documentary makers have been flocking to Shanghai to capture on film the story of this Port of last Resort.

To review some of Ron Gluckman's other reports from China, please click on China page.

Or read the amazing story of the oldest Jew in China.

Old Shanghai picture from unknown photographer. Rest by Ron Gluckman

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]