The War Goes On. And On.

A quarter of a century on, you can still see the tanks and tunnels everywhere in Vietnam. The war may be over, but the marketing goes on in a country with precious little to profit from other than the painful memories of the past

By Ron Gluckman/Saigon, Hanoi, Hue and Danang

EATH ONCE RAINED DOWN FROM THE MARBLE MOUNTAINS, filling the picturesque bays and valleys below with misery. Nowadays, the limestone caverns are crowded with jubilant tourists eager for a peak inside the rocky outpost that was the secret command center for this mad, main stage of the Vietnam War.

Besides housing a huge guerilla garrison that operated safely yet within easy striking distance of the American forces in Danang, the mountain caves also offered sleeping quarters, kitchen and a full field hospital.

Carpets of barbed wire, massive lots filled with tanks and bomber fields dominated the view from these mountains in those tragic days. The sky was filled with the nauseous fumes of petrol, burning flesh and napalm. Now, the air is clear, filled with the chatter of children. And the view from this infamous outpost in Central Vietnam has become one of hope, and fledgling prosperity.

Underneath a canopy of greenery, upon a white sand beach stretching around a picture-postcard bay, sits the Furama Resort Danang. Tranquility is the order of the day at Vietnam's first luxury resort. Yet close your eyes, and the sand seems to shake. You can almost hear the bomb blasts and cacophony of war.

Some of the

fiercest battles of the Vietnam War were fought in the shadows of these hills, and the

grim imprints remain firm upon the sand. In fact, that’s part of the attraction for

many visitors. In Vietnam, a country torn by over a century of strife, war memories are

painfully prevalent. But, as the country increasingly opens up to tourists and the hard

currency they bring, many are mining profit from those painful memories.

Some of the

fiercest battles of the Vietnam War were fought in the shadows of these hills, and the

grim imprints remain firm upon the sand. In fact, that’s part of the attraction for

many visitors. In Vietnam, a country torn by over a century of strife, war memories are

painfully prevalent. But, as the country increasingly opens up to tourists and the hard

currency they bring, many are mining profit from those painful memories.

Alongside this serene beach in central Vietnam, reminders of the US war are everywhere. You hardly need to stir from a beach chair to spy hangers that served helicopters and bombers, as well as the barbed wire skirting the former landing strips. Like so much of Vietnam, everything seems left in freeze-frame from a quarter of a century ago, when American troops fled, South Vietnam fell to the communist forces from the north and the horrendous civil war came to an end. Back then, amidst all the anguish, this was an oasis of tranquility, a lovely stretch of sand known as China Beach.

The name was celebrated by thousands of GIs, who welcomed the respite from the war offered by the cool sands of China Beach. Later, the name became known to millions of viewers of the hit TV show, "China Beach," eventually aired in 50 countries worldwide. But in Vietnam for two decades, the beach was simply called My Khe; China Beach was considered another imperialistic icon.

"For years, we didn't use the name, because of the bad feelings," admits Luong Minh Sam, Director of the Tourism Department of Danang. "But now we see the benefit." His office has ambitious plans for the infamous beach and several adjacent areas. A golf course is set to bloom upon the grounds of the old marine aircraft base, while approval has been given to several other beach resorts and retirement villas aimed at rich Japanese and Taiwanese. "We're calling the entire area China Beach, because that is a name everyone knows.

"We're promoting all the war history, but American tourism is really our aim," adds Luong. He explains the wisdom thusly: "Six million Americans were directly involved in the Vietnam War, and 20 million more were indirectly involved. That's a big market for use."

Marketing war

memorabilia is a boom industry in Vietnam, but it's not solely an American attraction.

French tourists still comprise the greatest number of visitors to northern Vietnam, where

they gleefully recall the glories of the colonial age, when Hanoi was capital of French

Asia, says Richard Kaldor, general manager of the Hotel Metropole, a magnificent old hotel

run by the French chain, Sofitel. But they also flock to desolate Dien Bien Phu, site of

the stunning French defeat by Ho Chi Minh's ragged jungle troops.

Marketing war

memorabilia is a boom industry in Vietnam, but it's not solely an American attraction.

French tourists still comprise the greatest number of visitors to northern Vietnam, where

they gleefully recall the glories of the colonial age, when Hanoi was capital of French

Asia, says Richard Kaldor, general manager of the Hotel Metropole, a magnificent old hotel

run by the French chain, Sofitel. But they also flock to desolate Dien Bien Phu, site of

the stunning French defeat by Ho Chi Minh's ragged jungle troops.

The French join not only Americans, but also the Chinese and Russians in revisiting a source of continual conflict. Every big city in the country claims at least one site showcasing Vietnam's centuries of struggle against a succession of colonial and neighboring powers. Networks of tunnels that once took guerrillas from engagement to escape are now overrun by tourists. Prisons have become first-class attractions, complete with souvenir stands. And the DMZ - a barren stretch of napalm-burned, mine-pitted terrain - might more accurately be renamed the De-Monetary-Zone, since this tourist trap sucks big bucks from military buffs.

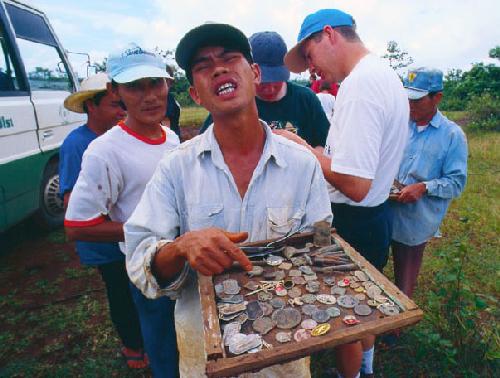

Local entrepreneurs long ago jumped on the war memorabilia bandwagon. Saigon street artists started the craze by crafting toy tanks and planes from scraps of Budweiser and Coca Cola cans. Dog tags and jewelry made from bullet shells soon followed. For years, one of Vietnam's major exports must have been fake Zippo lighters, copies of those carried by American GIs, inscribed with lewd or lonely messages of desperation. Put all the tourists with "authentic" army-issue Zippo lighters in a line and it would easily surpass one comprised of the mass of people claiming genuine chunks of the Berlin Wall.

Marketing such painful memories - an estimated 3 million Vietnamese died in a decade of conflict with the Americans alone - means that old wounds must be reopened, and cleansed. In the process, parts of the country that were most entrenched, particularly in the hardened north of the country, have also opened up. This is a welcome change from just a few years back, when early tourists found that visits to the north of former Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, often involved police hassles, endless red tape and inexplicable entrance fees.

Without a doubt, Vietnam has grown friendlier to foreigners; 1.6 million visited in 1996, and arrivals the next year soared 12.5 percent, to 1.8 million. While that's a trickle compared to the multitudes swarming nearby Thailand, the relative scarcity of visitors is part of Vietnam’s appeal. Many come for the deserted beaches, where seafood is sold for a pittance. However, tourism is expanding inland and north from the Mekong Delta, where ancient cities, delightful colonial villages and unexplored scenic wonders all help to make Vietnam the hottest new destination in Asia.

Nowhere are the liberal attitudes more apparent than in central Vietnam, the slender cord of land connecting the distinct northern and southern halves of a nation that has long been divided. Besides two major cities - Hue and Danang - this region boasts magnificent palaces, ancient ruins, eye-catching mountains, rivers lined with lush rice fields, undeveloped beaches, and one of Southeast Asia's oldest, and quaintest, international settlements, Hoi On.

Most spectacular of all is Hue, considered by many guidebooks to be the prettiest city in all of Vietnam. Surrounded by ancient citadel walls and home of the famed Forbidden Purple City, Hue boasts more than enough picturesque temples, pagodas and palaces to keep tourists in Kodak memories for months. Yet equally popular are the tours of the nearby Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

"We're full

every day," says tour operator Cu Phan. A former truck driver for the American

troops, he cannot understand the attraction to the barbed wire and bleak terrain of the

five-kilometer swatch of scarred land cutting across Vietnam, from the Laotian border to

the South China Sea. Cu Phan notes that these dreary tours cost five times as much as the

scenic boat trips he offers along the Perfume River, where pagodas and palaces are perched

at every bend.

"We're full

every day," says tour operator Cu Phan. A former truck driver for the American

troops, he cannot understand the attraction to the barbed wire and bleak terrain of the

five-kilometer swatch of scarred land cutting across Vietnam, from the Laotian border to

the South China Sea. Cu Phan notes that these dreary tours cost five times as much as the

scenic boat trips he offers along the Perfume River, where pagodas and palaces are perched

at every bend.

In contrast, the DMZ Tours are dusty and downright depressing. Most tours start in Dong Ha, capital of Quang Tri province, where military buffs get their first grand view of the battlefields they saw on the TV newscasts. They find plenty to gawk at. US tanks have been left to rot alongside railway tracks on the outskirts of town, guns purposefully left in a downward position, symbolic of the American defeat, the guide points out. Later, there are bombed churches and sad, skeletal bridges.

Still standing is the Rockpile, the imposing 230-meter stone hill where a clutter of nervy US Marines called in air strikes from the very midst of enemy territory. The isolated fortress could only be serviced by helicopter drops. It was protected by fields of mines, which still explode, wrecking misery on a population that has known nothing in its lifetime but war. This point is hammered home as the tour bus passes towns constructed largely from the horrific refuse of the American war. Still, one cannot help but marvel at the ingenuity of the recyclers: shell cases have become planter boxes, fencing and siding. Even the snap-together metal tarmac of some airfields has been pulled up and hammered into roofing.

The highlight of the tour comes in the Quang Tri Tunnels, among a network of secret tunnels left from the war. Most served terrorists and assassins, working most effectively behind enemy lines. These at Vinh Moc, though, were built by villagers to escape relentless carpet bombing by B-52's. Only one tunnel, the deepest, remains intact. Over 600 people lived in this tunnel from 1968 to 1972.

Back in the bus, tourists roll past a procession of graveyards. Yet visitors find the tours evocative, rather than grim. Scratching his head back in Hue, Cu Phan says the choice is just one more mystifying lesson for a fledgling tourist industry that started from scratch during the last half-decade. No worries, he quickly adds, as business of any kind is considered welcome progress in Hue. "Things here were really bad when the Americans left. We had to stay here and suffer it through with the VC. There were many problems, so many restrictions. But now it's OK. Vietnam is moving again."

And how. The change of pace is most apparent in Hanoi, the stodgy communist capital of the north. Visitors from a decade ago may recall Russian-style parades, a scarcity of restaurants and guards at every doorway. But even Hanoi has been brightening up to the prospects of tourism in recent years, and that’s good news to the slow trickle of pioneers who have given this destination a try.

Hanoi is perhaps the most delightful city in Asia, with broad, tree-lined boulevards radiating around a series of lakes, and stately government buildings that are like timepieces from a glorious past. "Hanoi is a marvelous treasure, one of the last untouched capitals left in Asia," says Richard Kaldor, general manager of the Hotel Sofitel Metropole. Opened in 1911, the stunning white colonial inn serviced scores of diplomats and generals during the long war years. During the air campaign by the Americans, guests were assigned personal bomb shelters dug into the pavement outside the hotel.

Around the capital, one can find ample reminders of the French and American wars. The best place for military buffs is probably the Army Museum. It's not well marked, but is easy to find. Alongside is the hexagonal Flag Tower, part of an early 19th century citadel. In front of the cluster of buildings is a huge pile of what appears, at first glance, to be rubbish: twisted hunks of metal and other debris. Actually, this is one of the exhibits, a heap of bombshells, tank tracks and old jet wings. Inside are blood-drenched paintings and gory photographs. Yet they are popular; the Army Museum is in the midst of a major expansion.

Indeed, from top

to bottom, Vietnam is repackaging its collection of war museums, dusting away some of the

dowdy propaganda and sprucing up the exhibits for greater international consumption.

Indeed, from top

to bottom, Vietnam is repackaging its collection of war museums, dusting away some of the

dowdy propaganda and sprucing up the exhibits for greater international consumption.

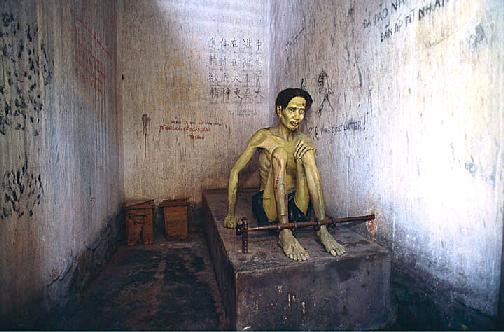

In Ho Chi Minh City, the biggest crowds visit the War Remnants Museum to view a grisly menage of photos of torture and shocking war crimes. Included is a mock prison with tiger-cage cells, emaciated models, and evidence of beheadings and dismembering. As ghoulish as it now seems, some of the most blood-wrenching exhibits have been removed or toned down. Likewise the name of the place, which used to be the Museum of American War Crimes.

War buffs will find even better pickings at Ho Chi Minh’s Military Museum, which sports a fine array of American and Vietnamese military hardware, including tanks, shells, bombs and the wreckage of downed aircraft.

For those interested in digging deeper into Vietnam’s long history of conflict, the Revolutionary Museum offers over a dozen rooms of resistance memorabilia dating back to the first campaigns against the French in the 1800s. Besides old weapons, medals, uniforms, homemade bombs and booby traps, there are fine archival pictures. Here, and at all the war museums, it’s easy to shop for souvenirs that include dogtags, military hats and clothing, knives, medals and lighters; mostly fake.

Former Saigon abounds with less grisly reminders of the war era. A mandatory stop is the rooftop of the Rex Hotel, a famous hangout for American officers and war correspondents in the 1960s and 1970s. The regular war briefings, in which officers boasted of inflated body counts was dubbed, "the Five O Clock follies." The charts are gone but the gaudy, Vegas-like rooftop furnishings remain, and the view is strikingly familiar. From the Rex rooftop, the bustling city down below looks much as it did decades ago, swarming with motor bikes and the hustle of thousands of hungry entrepreneurs in the new Vietnam.

Perhaps that's why it seems ironic that hottest attractions in Vietnam seem to recall the dark, old days. Among a slew of nightclubs with war-time monikers, the most successful is the Apocalypse Now chain. And the most popular tourist site in town remains the Chu Chu tunnels, where up to five thousand guerillas crawled through a maze of cubbyholes too tight for the America forces to follow. The tunnels have been enlarged for the tourists, who flock to the caverns that survived the fury of half a million US bombs. Eerily, you can still hear the sound of gunfire.

That's because nearby is another tourist attraction: the National Defense Shooting Range. For five dollars, you can fire off a few rounds on an American M-16, or the AK-47s favored by the Vietnamese who won the war. "C'mon and try it," urges one attendant. "It's your chance to be a part of the war."

Ron Gluckman is an American journalist who has been based in Hong Kong for eight years, roaming widely around Asia for a variety of publications, including the Wall Street Journal, Time, Newsweek, Asiaweek, Discovery, Mode and the Sydney Morning Herald. For another story from Vietnam, turn to China Beach.

The photos on this page are by Graham Uden, a British photographer in Hong Kong who often works with Ron Gluckman. For other samples of Uden's work, see McChina, the Americanization of China.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]