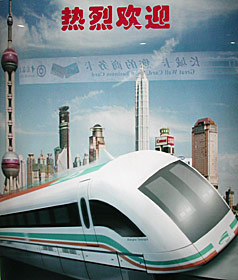

Is it a Bird? A Plane?

Nope, only Shanghai's flashy new Maglev, the world's fastest train. Way ahead of its time seven decades ago, the still-futuristic magnetic levitation system may yet redefine travel everywhere.

By Ron Gluckman/Shanghai,China

LIKE MANY ON THE MAINLAND, I was on the move over the Chinese New Year. My flight lifted off early on the last morning of the Year of the Horse, touching down at the airport eight minutes later. Yet it never left the ground.

My flight - that's what it was called - was aboard Shanghai's spanking-new

Maglev (magnetic levitation) train, the world's fastest, most futuristic

passenger line.

My flight - that's what it was called - was aboard Shanghai's spanking-new

Maglev (magnetic levitation) train, the world's fastest, most futuristic

passenger line.

Longest-awaited, too, since it's been an astonishing seven decades since the invention of the process that was finally put to a test on the next-to-the-last day of last year, when Premier Zhu Rongji took an inaugural ride with Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder of Germany, which helped fund and build this line. Now, common cadres were having a turn.

Local media called them "joyrides," these series of trial runs to the international airport in Pudong, across the river from Shanghai proper, that add a bit of flash to the Spring Festival. They certainly live up to the billing.

Smiles abound inside the sleek train as, with a breathtaking whoosh, it rockets to 300 kilometers per hour in two minutes flat. Overhead, like a giant scoreboard, an LED blinks out our record-breaking progress till we top 430 kph.

"It's wonderful," says Lu Cong Mei, who came with her husband, sister and several other relatives. Lu plops into a window seat with her shopping bag of thermal underwear from China's famous undergarment maker Three Gun (motto: "Cozy and Elastic) and gleefully watches scenery flash past like in a Coyote and Roadrunner cartoon.

"Amazing," she comments afterwards. "I'll tell all my friends to try it." Grandson Dai Wei, 14, adds: "It is fast, really fast. Way faster than I expected. It felt like flying."

Indeed, the Maglev is faster than any speeding locomotive precisely because it's

as much like a plane as any railroad we've known.

Indeed, the Maglev is faster than any speeding locomotive precisely because it's

as much like a plane as any railroad we've known.

True, the train has no wings, but no wheels or engine, either. Transrapid, the German firm that developed the system, describes the Maglev as "the first fundamental innovation in the field of railway technology since the invention of the railway."

Magnets are the attraction. First, powerful magnets lift the entire train about 10 millimeters above the special track, called a guideway, since it mainly directs the passage of the train.

Other magnets provide propulsion, and braking, and the speeds - up to 500 kph in test runs; a good 60 percent faster than the renowned Bullet Trains - are attained largely due to the reduction of friction.

Is there a need for such speed? Certainly not on such a short sprint, barely 30 kilometers from the subway in Pudong to the airport.

And not at the cost, note critics. The Pudong line, which should go into operation by the end of this year, is unlikely to ever recoup its $1.2 billion investment.

A high-speed link between Beijing and Shanghai, among several additional Chinese lines under consideration, might cost $22-30 billion, or nearly as much as China intends to invest in all rail infrastructure nationwide in its current five-year plan.

Still, critics miss the point. And the thrill. The Maglev isn't about getting from point A to B in Pudong. Rather, it's the ride, a glorious glide, from the past to the future.

And where this new train might take us, not simply San Francisco to Los Angeles, say, in less than two hours, but in a flash, from the mundane motion of nowadays to the hyper-speeds of Tomorrowland.

That's the rush I feel stepping aboard Shanghai's sleekly-contoured train, a

feeling of futuristic fervor mixed with nostalgia for all those comics and

sci-fi novels from boyhood. There is good reason, since the Maglev's technology

is actually rather dated. German inventors patented the basic system way back

before World War II.

That's the rush I feel stepping aboard Shanghai's sleekly-contoured train, a

feeling of futuristic fervor mixed with nostalgia for all those comics and

sci-fi novels from boyhood. There is good reason, since the Maglev's technology

is actually rather dated. German inventors patented the basic system way back

before World War II.

That's another point of critics. In the ensuing seven decades, magnetic levitation trains haven't moved much closer to reality.

A test track in northern German was built nearly 20 years ago, but even the Germans have shied away from launching a commercial magnetic levitation line because of the cost.

"The huge investment just doesn't make sense in a country like Germany, with a well-developed rail system," concedes Dr. Wolfgang Rohr, German Consul General in Shanghai.

"But for countries like China - or the United States or Australia - they could jump to this new technology which has huge potential." He points out that the Maglev is pollution-free, with no exhaust.

Later, I join a group of excited old-timers in the countryside, midway to the airport. We watch the Maglev blaze silently past. That's another advantage; hardly any noise.

"In Germany, we've been having endless

discussions about this," notes Eckhard Schneider, a German tourist riding

the Shanghai Maglev over the holidays. "Here, in China, they just do

it!"

"In Germany, we've been having endless

discussions about this," notes Eckhard Schneider, a German tourist riding

the Shanghai Maglev over the holidays. "Here, in China, they just do

it!"

Adds companion Ulli Schonart: "They built this all in less than two years. Amazing! In two years in Germany, we'd just have a plan for the evacuation of the birds along the way."

Long hopelessly ahead-of-its time, the Maglev could finally come-a-time. Germany may soon commit to its own line, possibly from Dortmund to Düsseldorf in time for the 2006 World Cup, or a Munich airport express.

Meanwhile, in the United States, a $1 billion-funded US pilot project has settled on two finalists: a 47-mile Pittsburgh system and a 40-mile track linking Baltimore and Washington, DC.

On the other side of the country, Maglev-backers are lobbying congress to fund a 92-mile circuit between three Southern California airports that could be expanded to a 273-mile web designed to relieve the region's gridlock.

The US proposals would all utilize independently-patented American Maglev technology.

All that is a big if, though. For now, Shanghai is the first out of the tracks, and early-riders give the train-plane two thumbs-up . "I'm proud that Shanghai has this when nowhere else in the world does," says Lu, as we glide almost soundlessly to our arrival at the new Pudong international airport.

On a journey of firsts, here's another. Lu has never seen the airport. Which isn't that surprising, considering she, like the others in her family, and most in China, for that matter, have never taken a flight.

Until now.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has been roaming around Asia since 1991, when he was based in Hong Kong. Since 2000, he has been based in Beijing, covering China for a wide variety of publications including the Asian Wall Street Journal, which ran this in the Weekend Edition of February 21-23, 2003.

Despite much ballyhooed plans for new maglev lines between Beijing and Shanghai, as well as the shorter run from Shanghai to Hangzhou, China reiterated its plans for high-speed rail, but with the surprise announcement in spring 2006, that it has successfully tested and planned to proceed with its own style of Maglev. Check back for more news on the progress.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]