Outpost of Decadence

Anyone advocating greater contact with Burma as a way of pushing reform, only need look at the borders for results. They are booming - with casinos, copy CDs and movies, as the old drug lords move up the illicit investment chain, with black-market emporiums modeled on a seedier, mob-style Las Vegas.

By Ron Gluckman / in Burma's Golden Triangle

E

NGAGEMENT. OR ISOLATION? The great debate rages on and on about Burma, long ago one of Asia's richest nations, now a basket-case that regularly bounces back into the news for all the wrong reasons.Those contemplating the value of greater contact with Burma as a way of facilitating change need look no further than Tachileik to see the results. But this strange hybrid town will likely fuel rather than resolve the debate.

Ten years ago, this quiet settlement across the river from Thailand's Mae Sai claimed only a few dirt roads and a grubby market with wilted vegetables. Nowadays, thanks to trade across a bridge to Mae Sai, the town is a center of commerce, of a type.

Day-trippers load up on bootleg

cigarettes and cheap copy CDs. Hard rock, pop and punk discs run 50 cents a pop,

while $2 buys Hollywood blockbuster flicks on DVD from wall-to-wall music and

movie stalls at Tachileik's huge marketplace.

Day-trippers load up on bootleg

cigarettes and cheap copy CDs. Hard rock, pop and punk discs run 50 cents a pop,

while $2 buys Hollywood blockbuster flicks on DVD from wall-to-wall music and

movie stalls at Tachileik's huge marketplace.

"Sex video?" shouts one salesman, pushing forward a tray filled with tapes and what appear to be sex toys of scary design.

Dodging him, I retreat to a dim back alley where stalls display horns, skulls and claws of various animals, many endangered boasts one vendor, thereby putting up the price.

Such tawdry goods would not be seen elsewhere in Burma, where the release of rock music remains strictly regulated and was altogether outlawed until not long ago, and Western movies are still banned. Yet these excesses abound in Tachileik, along with the town's greatest money spinner -- gambling.

Tachelik's grand gaming hall, the Regina Hotel and Casino, sits high on a hill with a sweeping view that sums up just what a quagmire Burma has become. Just below sprawls the lush green grass of a neatly-trimmed golf course, off-limits, of course, to the bare-footed and shabbily dressed locals who tend it.

Likewise entry to the Regina, but

some might find work next door, where a tribal petting zoo pulls in curious

tourists thanks to the main attraction: long-neck women, so nicknamed because

females in the tribe pile brass rings atop their shoulders, seemingly stretching

their necks to giraffe-like proportions.

Likewise entry to the Regina, but

some might find work next door, where a tribal petting zoo pulls in curious

tourists thanks to the main attraction: long-neck women, so nicknamed because

females in the tribe pile brass rings atop their shoulders, seemingly stretching

their necks to giraffe-like proportions.

If this freak show is

distasteful, one can return to the Regina, where over the golf course rises the

signature gilded spire of a Burmese stupah, or paya, symbol of all that is good

and

righteous about Burma.

In Tachileik, everything seems twisted from the national routine, in deplorable but also delightful ways. Motorbike rickshaws tour temples being rebuilt faster than the government has ever shut them down elsewhere.

And the recent arrest of democracy advocate Aung San Sui Kyi, like other news from capital, has no impact here.

Even bomb explosions in

Tachileik in the week before Ms. Sui Kyi's arrest hardly raised local eyebrows.

"That was a few miles outside Tachileik," explains one native,

discounting a revival of

the guerrilla wars that plagued this region for decades.

"They weren't rebels," he

adds, lazily picking his teeth, "just people who had their

reasons."

"They weren't rebels," he

adds, lazily picking his teeth, "just people who had their

reasons."

Indeed, there is a certain off-handed, outlaw manner about Tachileik and other border posts in the Golden Triangle, where Burma's military regime long ago ceded control to warlords rather than battle them.

Drug-running was the trade of choice in the past, but increasingly those same warlords have moved up the investment food chain, from opiates to operations like resorts, casinos and tourism.

It might seem reminiscent of the Mob move to a stretch of barren desert in western America, but this is hardly Las Vegas. Forget dancing girls, free drinks, lounge acts. The lure to Burma's casinos is one-dimensional.

Glaringly so at Paradise Resorts

Golden Triangle, another hotel-casino complex in this remote but breathtakingly

picturesque part of Burma. You can see the orange-pink tiles of the Paradise

roof poking through the jungle for miles; in fact, it's the only thing visible

for miles in the whole country.

Glaringly so at Paradise Resorts

Golden Triangle, another hotel-casino complex in this remote but breathtakingly

picturesque part of Burma. You can see the orange-pink tiles of the Paradise

roof poking through the jungle for miles; in fact, it's the only thing visible

for miles in the whole country.

And talk about exclusive. It sits on a kind of island, cut off from any other part of the country. Entry is only by boat from Thailand.

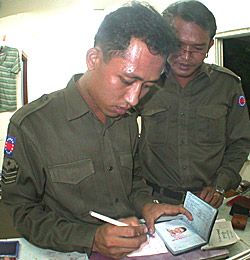

In fact, the Paradise isn't really in Burma, nudge-nudge, wink-wink. That's because this isn't really an official border crossing. In a land filled with contradictions, here's yet one more: non-Thai foreigners hand over passports and the same $5 fee you pay for a day pass in Tachileik, picking up an unstamped passport upon their return.

Or one can pay $10 per night, for up

to a two-week stay at the Paradise, although you would have to be pretty

hard-core. Besides the casino, there is nothing on the Burma side for 150

Or one can pay $10 per night, for up

to a two-week stay at the Paradise, although you would have to be pretty

hard-core. Besides the casino, there is nothing on the Burma side for 150

kilometers other than an eerily inappropriate seven-story tall Buddha statue

that Thais pray to before hitting the tables, and a tiny convenience store

called 7-Elevei.

Practically all the punters come from Thailand, along with the food and workers. Likewise funding for the casinos, and more on the way (including two reportedly planned for the pristine Adaman Sea, one a nudist resort).

Anti-engagement activists can target oil and textile companies doing business with Burma, but greater impact might come from a bit of Thai diplomacy -- at the gaming tables. Exactly how much dough the generals rake in from the slots and baccarat is unknown, but one study reckoned Thais wager over $2.5 billion annually in casinos in neighboring states, mainly Burma.

As a measure of Burma's stake, last year when these two neighbors exchanged mortar fire, a regular affair in the Golden Triangle, all borders were abruptly sealed. Except those allowing access to the cash-generating casinos.

Like everything else in Burma, even

sleazy casinos can have a silver lining. "Things here are very relaxed and

easy," says Anit, who makes a bit of money selling postcards and guiding

tourists around Tachileik's gleaming Shwedagon, a near-exact copy of the

country's most revered stupa in Rangoon.

Like everything else in Burma, even

sleazy casinos can have a silver lining. "Things here are very relaxed and

easy," says Anit, who makes a bit of money selling postcards and guiding

tourists around Tachileik's gleaming Shwedagon, a near-exact copy of the

country's most revered stupa in Rangoon.

His income isn't great, he notes, but he's happy he moved down from Mandalay. "Around here, everything is Thai, the people, the food, even the money."

Indeed, the much-ridiculed Burmese kyat has no hold in these parts. Likewise the turmoil and troubles of Yangon.

Reform, the way democracy advocates talk about it, may never roll into Tachileik. But the regime rarely visits, either.

To locals as well as casino bosses, that suits them fine.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who is based in Beijing, but who roams around Asia for a number of publications, such as the Asian Wall Street Journal, which ran this story in June 2003.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]