Shangri-la's new horizon

In typically incongruous fashion, China branded the tiny town of Zhongdian as Shangri-la, in order to cash in on the connection. Yet, after the obvious rebirthing pains, this picturesque Tibetan community makes a fair claim to being a Himalayan paradise.

By Ron Gluckman/ in Zhongdian, Yunnan Province

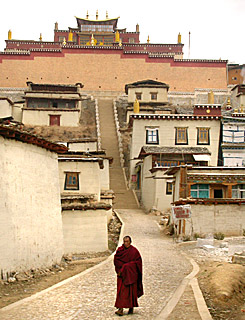

THE OWNER OF THE SONGTSAM HOTEL might seem your typical seeker of Shangri-la, the fictitious mountaintop Utopia of James Hilton’s novel, "Lost Horizon." This big-city television producer regularly flees work pressures by retreating to the serene lodge he opened three years ago.

"I come every three months," he says. "It’s a peaceful place, not just for my guests, but for me, too."

The setting seems ideally suited to Shangri-la, lately as much a buzzword for

inner tranquility as scenic surroundings. Next door is an old Tibetan monastery,

filling the air with the smell of incense and sound of chants. Shaggy yaks drag

plows across nearby fields, turning loamy soil into fertile oatmeal. Overhead

rise mountains in all directions, topped with snow, looking like vanilla

sundaes. The air is clear, the sky teardrop blue.

The setting seems ideally suited to Shangri-la, lately as much a buzzword for

inner tranquility as scenic surroundings. Next door is an old Tibetan monastery,

filling the air with the smell of incense and sound of chants. Shaggy yaks drag

plows across nearby fields, turning loamy soil into fertile oatmeal. Overhead

rise mountains in all directions, topped with snow, looking like vanilla

sundaes. The air is clear, the sky teardrop blue.

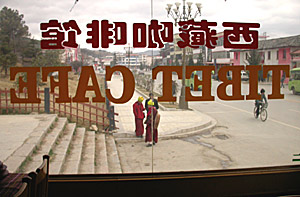

And should anyone harbor doubts that this really is Shangri-la, three years ago, the Chinese government proclaimed it so. Ending a fierce rivalry that rippled through Yunnan and Sichuan province towns along the rugged Tibetan border, Zhongdian was anointed the official Shangri-la.

Much more was at stake than bragging rights as a highland paradise; the tourism potential is massive. Already millions come each year to a remote part of western China that was off-limits to foreigners just a decade ago. Flights only launched in 1999, and then just once a week in summer.

Now, there are traffic jams in Shangri-la, as tourists and touts flood this once-isolated village, either to cash in on its newfound fame or get an instant dose of idyll. Not so the owner of Songtsam, no Shangri-la carpetbagger.

Baima Dorje, a well-known documentary maker in Beijing, is an ethnic Tibetan and lifelong booster of Zhongdian – his hometown. "For years, I told all my friends about this place, and tried to get them to come.

"I don’t know anything about running a hotel," admits

Dorje, who only opened the Songtsam when no friends could be enticed to do the

same on a site fronting the exquisite 17th century Song Zhangling

Monastery. Dorje grew up here, in his family home.

"I don’t know anything about running a hotel," admits

Dorje, who only opened the Songtsam when no friends could be enticed to do the

same on a site fronting the exquisite 17th century Song Zhangling

Monastery. Dorje grew up here, in his family home.

"I just wanted to show the beauty of this place to everyone."

Dorje is part of a new local craze for Shangri-la, which had long been a global obsession. Credit James Hilton, who set his 1933 novel, "Lost Horizons," in a mountaintop paradise, where residents lived harmoniously and at great length, reveling in learning, inner peace, and the great meaning of it all. Four years later, Frank Kapra’s sumptuous film took the Utopian dream to the wide screen; the longing for this mythical paradise only loomed larger with each passing decade.

China pinpointed Shangri-la via a long process of research. Candidates ranged across several craggy Chinese provinces and as far as Pakistan’s Hunza, Bhutan, Mustang and other Himalayan outposts. The crucial evidence remains controversial. Old stone tablets (in a museum in nearby Lijiang, itself a candidate for Shangri-la status) refer to a village called Xiang Ge Li La, which is how locals pronounce Zhongdian’s new name, Shangri-li-la.

Ben Hillman, author of "Paradise Under Construction: Minorities, Myths and Modernity in Northwest Yunnan," explains: "According to the experts, ‘Xiang ge’ means ‘inside the heart’ in the local Tibetan dialect, and ‘li’ and ‘la’ mean sun and moon respectively. Shangri-la therefore is conclusively shown to mean ‘to have the sun and the moon in your heart’." But he believes Hilton more likely misread "Shambala," a Tibetan word referring to a mythical northern paradise.

Local folklore tells of a plane crash in World War II, supposedly the

model for one that propels the characters to Shangri-la in the opening of

"Lost Horizon."

Local folklore tells of a plane crash in World War II, supposedly the

model for one that propels the characters to Shangri-la in the opening of

"Lost Horizon."

Guides offer to take me to the remote site, definite proof that this is Shangri-la. I never have the heart to point out that Hilton, who never visited China, published his book a decade before the crash that supposedly launched it.

No matter; paradise had been found. Now, the task isn’t so much marketing as maintaining it. "The proclamation created tremendous awareness," concedes Yeshi Gyetsa, a Tibetan who runs Khampa Caravan, one of the top local tour companies. "But also tremendous expectation, and pressure."

Nobody knows this better than A Wa, Director of the Tourism Bureau of Diqing Tibet Autonomous Prefecture, stretching over three counties that include Zhongdian and many rivals for the Shangri-la crown. In a spirit of conciliation – cynics say commercialism – much of prefecture is now referred to as the Shangri-la Area. With the designation in May 2002 came unimaginable challenges.

"Two years ago, 50,000 to 60,000 people showed up, every day," Wa recalls, "and we had nowhere to put them. We had them staying the spas, the schools, everywhere. One time, I had 28 tourists in my own home!"

Now, it’s no longer a problem, he enthuses. Hotels have sprouted up

faster than the mushrooms harvesting that used to drive the local economy, after

timber cutting was halted by a government ban.

Now, it’s no longer a problem, he enthuses. Hotels have sprouted up

faster than the mushrooms harvesting that used to drive the local economy, after

timber cutting was halted by a government ban.

Tourism is the new gold rush, and scores of new tiled lodges have laid stakes: from the Great Hotel of Good Luck and Happiness to the gaudy Holy Palace Hotel. In the hilly outskirts of town, Banyan Tree, a top Asian chain, has opened a luxury spa at Gyalthang Dzong Hotel. Several other high-end boutique chains have snapped up property.

Paradise Lost? Lest this seem a tragically familiar tale, Wa insists the precious qualities of Shangri-la won’t be trampled in a stampede of tourist traffic. Already regulations control construction in town, which must keep to traditional Tibetan style.

That didn’t prevent installation of Zhongdian’s greatest icon, or

eyesore, an enormous prayer wheel, 24 meters tall, spinning on a hill overhead.

That didn’t prevent installation of Zhongdian’s greatest icon, or

eyesore, an enormous prayer wheel, 24 meters tall, spinning on a hill overhead.

Down below, sits the town’s greatest gem, an old neighborhood of wooden houses and storefronts. This is old Zhongdian, and it appears untouched since horse caravans set out from Yunnan fields a century ago, carrying tea to Lhasa.

Recently, restoration has started on the district, with the Raven Pub being among the first establishments to open. Jason Lees and Amy Wright run the Raven and a trekking company, after relocating from Liang.

"We went to Lijiang for the first time as travelers in 1996 and fell in love with the place," Lees says. "In those days, it was a few cafes and the odd backpacker. If you put Yunnan in a search engine, you got like 40 hits, and 38 of them were botany expeditions in 1937."

Then Lijiang was discovered by group tours. Lijiang remains an almost fairytale town, but can resemble Hong Kong at rush hour. Lees fears that Zhongdian may repeat the process.

In unusually candid terms, Wa assures me that Lijiang is the role model, but only for what Shangri-la will never become. "I want to go back to the original feel of the Tibetan district, to capture the special characteristics of the Tibetan culture and people," he says. "No way will this ever look like Lijiang."

Wa’s proclamation is surprising, not for its conviction, but also

because Lijiang is often held up as a model for tourism across China. "It’s

too commercial," he explains. "I’ve been to Disneyland, to American

amusement parks. But they are all manmade. Here, it is all natural. There’s no

fence around Shangri-la. You have it all here, the Museum of Rivers, the Museum

of Mountains, and the Museum of Peoples, just one big natural museum."

Wa’s proclamation is surprising, not for its conviction, but also

because Lijiang is often held up as a model for tourism across China. "It’s

too commercial," he explains. "I’ve been to Disneyland, to American

amusement parks. But they are all manmade. Here, it is all natural. There’s no

fence around Shangri-la. You have it all here, the Museum of Rivers, the Museum

of Mountains, and the Museum of Peoples, just one big natural museum."

Indeed, everywhere you go, people talk about the Shangri-la brand, but a land of such cultural beauty and diversity would seem to need little marketing. A few miles from town, pasture opens to magnificent alpine meadows, framed by forest. Mountain snow feeds a trio of mighty rivers, the Yangtze, Mekong, and aptly-named Jinsha (Golden Sand). Villages are even more colorful. Besides Tibetans, the area is populated by Lisus, Naxis and Yis.

Returning from one expedition, the sound of singing is so loud, my companion and I hear it over the roar of passing tractors. Like sirens, the lilting voices lure us down a series of dirt roads, to a construction site. A huge hall is being built in Kochi Village, and the entire town has turned out to help.

The frame is up. Men balance on dirt walls, many stories high,

pounding piles of mud into place. Women in dazzling scarves, of red, orange and

maroon, work in bucket brigades, carting the clay up wavering planks. All the

time, to the rhythm of the pounding, the men chant in Tibetan: "Don’t

bring me dry mud, don’t bring me the wet mud, just bring me the right

mud."

The frame is up. Men balance on dirt walls, many stories high,

pounding piles of mud into place. Women in dazzling scarves, of red, orange and

maroon, work in bucket brigades, carting the clay up wavering planks. All the

time, to the rhythm of the pounding, the men chant in Tibetan: "Don’t

bring me dry mud, don’t bring me the wet mud, just bring me the right

mud."

The harmony, community, and cheerful singing all seem the very picture of Shangri-la. Long after we depart, the uplifting melodies keep ringing in my head. That night, my dreams are rich and vivid. In the morning, I wake in a surreal state, certain the singing has never stopped.

Out through my window, I see farmers working the fields around the Songtsam Hotel. Amidst the clanging of yak bells and calls of encouragement from tenders, echo distant chants from Zhangling Monastery. Morning prayers are being said. I cannot help thinking: you needn’t seek far to see this is Shangri-la.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter based in Beijing, who roams around Asia for a number of publications, such as Silk Road, the in-flight magazine of Dragon Airlines, which ran this story in October 2004.

All pictures by Ron Gluckman

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]