The Alternative Olympics

Every summer, the hardships and food shortages are forgotten as Mongolian nomads wandering one of the world's harshest environments all merrily congregate for the annual celebration of the Three Manly Sports

By Ron Gluckman / Mongolia

D

UST SWIRLS LIKE BROWN CYCLONES across the grassland in the distance, long before the riders break the horizon. Then, the ground heaves to the pounding of hundreds of hoofs, as horses surge for miles across the steppes.

The race course is a rainbow of color. Banners fly from carnival booths. Horse manes are pinned punk-style, with ribbons. Reins are studded with shiny silver. And riders in the world's largest horse race are wrapped in embroidered robes of blue, orange and magenta.

In the barren plains of Mongolia, where winters are ferocious, food is scarce and one can roam the range for days without seeing a sign of human settlement, there would seem to be no better test of mettle than simple survival. However, thousands of hearty descendants of Genghis Kahn compete in shows of skill and strength every summer at Naadam, a sports festival rivaling the Olympics as the Earth's oldest games.

Long ago, this was what constituted civilization: wrestling, horse riding and archery. Mongols maintain that their "Three Manly Sports" separate the real men from the boys.

The festival draws its name from the Mongol verb, naadah, meaning to play. Like life on the plains, even the games are grueling.

Children as young as five ride bareback for 15 miles in the horse races, which continue for two days. Only a handful join the "airag's five," the sacred winner's circle. Winning horses and riders are showered with fermented mare's milk, or airag, the national nectar. Riders repeat an old "ghingo" chant before the starting gun, then push horses to a feverous pace by shouting "goog." The fastest horses are honored with poetic names from Mongolia's glorious past.

Little seen by most outsiders throughout its history, Naadam has continued in modern times under the watchful eyes of observers from Russia and China, who split the Mongolian nation in half in the 1920s. In the Chinese-ruled region of Inner Mongolia, Naadam festivals have been held irregularly, often secretly and in outlying areas, due to official bans imposed periodically on displays of native culture.

In the Republic of Mongolia, which in 1990 became Central Asia's first democracy, the mid-summer festival was initiated by Genghis Kahn in the 12th Century. Even under Soviet rule, Naadam remained the Mongol main event, slyly scheduled to begin July 11, for seven decades known as National Day, commemorating the People's Revolution of 1921 - which made Mongolia the second communist republic after Russia.

Mongolia's more recent democratic revolution marked the departure of the former Soviet

hosts and opened the festival to western eyes for the first time. "The crowd is much,

much smaller," said Hodolmor, of the opening parade. About 100,000 Mongols

congregated in the capital of Ulan Bator for the festival, but only a fraction attended

opening ceremonies. "Before, we were forced to come with our worker groups. But now,

with freedom, it's not forced," Hodolmor added.

Mongolia's more recent democratic revolution marked the departure of the former Soviet

hosts and opened the festival to western eyes for the first time. "The crowd is much,

much smaller," said Hodolmor, of the opening parade. About 100,000 Mongols

congregated in the capital of Ulan Bator for the festival, but only a fraction attended

opening ceremonies. "Before, we were forced to come with our worker groups. But now,

with freedom, it's not forced," Hodolmor added.

Fewer spectators may flock to Sukhbator Square, a massive city plaza larger even than Moscow's Red Square, yet enthusiasm showed no sign of being diminished. Early risers watched a parade of bands and red-and-black toy soldiers marching with more spit-and-polish precision than anything this side of Buckingham Palace. In a tribute to Genghis Kahn, restored to national hero status after 70 years of subjugation under the Soviets, an entire brigade of Mongol warriors roar past, in Hun helmets, brandishing old swords and banners.

It's only fitting that horses maintain a place of prominence in this national festival. Horses, pictured on the national seal, are much more than mere beast of burden in Mongolia. Horse milk is a staple of the Mongol diet, in the form of butter, cream and cheese. When fermented, mare's milk is turned into a kind of wine and airag, a frothy beer-like beverage that is highly prized and consumed in copious quantities by Mongolians, who consider drunkenness, among males anyway, an honorable as well as enjoyable escape from the harsh realities of nation that claims both the southernmost permafrost and northernmost desert.

Airag is offered to anyone who visits a ger, or yurt, as the mobile Mongolian tent-like huts are known. And huge vats of airag were brewing beside thousands of tents in the outskirts of Ulan Bator, where the country people camp during Naadam. The races are held nearby, and the riders spend several days grooming horses, braiding manes and preparing riding outfits. Few nomads own more than one change of clothes. A Mongol explained through a translator, "When my boot takes water, I make new one."

Although

functional, Mongol dress is rarely drab. Standard garb on the steppes is a woolen robe,

worn over layers of felt, multiplying as the mercury drops as low as -25 c. This is

everyday wear, but Mongols all maintain at least one outfit for special occasions.

Although

functional, Mongol dress is rarely drab. Standard garb on the steppes is a woolen robe,

worn over layers of felt, multiplying as the mercury drops as low as -25 c. This is

everyday wear, but Mongols all maintain at least one outfit for special occasions.

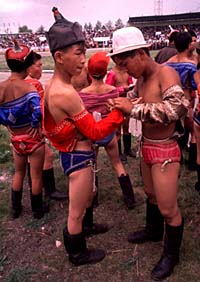

Naadam brings out the best, in brilliant shades of orange, magenta and violet. Felt hats, the norm on the range, are replaced by traditional pointy-topped caps, or priest-like headgear. Ceremonial clothing also plays a major role in the pomp at Naadam's premier event; wrestling.

This is the national obsession. Traffic comes to a halt in Ulan Bator during televised bouts, which draw record ratings. Champions become household names on the plains. The most revered wrestler, Bayanmonh, a ten-time national champion, travels in the company of a nomadic entourage that would put Prince to shame.

Naadam Stadium is filled to capacity for the wrestling competition. The start is a magical sight. The field is empty when the national anthem is chanted by the crowd. Then, without warning, hundreds of men suddenly toss aside robes, and scream madly as they bound down into the arena, stripped down to little more than leather boxing shorts.

Fifteen hours a day, for two days, they face off in pairs, scores of meaty Mongols circling in fierce single-elimination battle. From 512 men, the field is cut in half, than cut again, over and over, until only the top two combatants of the tundra are left standing.

Mongol wrestling offers little excitement to the uninitiated. The two men grasp shoulders and spin slowly in circles. Muscles bulge, but nothing happens. Men seem motionless for 10 minutes, before one makes a desperate dash for a leg hold. Then, as suddenly, the match can end within seconds. Unlike Sumo, which it sometimes resembles, or Olympic wrestling, there is no margin for error in Mongol wrestling. Should any part of the body touch the ground, the match is over.

Afterwards, the winner grabs his hat and tips it to the loser. Both men begin wildly flapping their arms, as they bounce on bent knees to the platform of honor. This is the traditional flying eagle dance, which every contestant performs before and after the bout.

Animal imagery figures in every facet of the wrestling. Winners in the fifth round are proclaimed falcons, and have their praises sung by seconds. They become elephants in the sixth round, and lions at the eighth. A winner of several championships becomes a giant.

Outside the

wrestling arena, archers take aim at tiny targets in the third-most manly sport of Mongol

folklore. A line of 360 leather rings run in a line perpendicular to the bowman in the

middle of two rows of dirt mounds. Men shoot at a distance of 75 meters; women from 60

meters. The object is to barely clear the first mound and pierce the targets. A scattering

of red rings bring bonus points.

Outside the

wrestling arena, archers take aim at tiny targets in the third-most manly sport of Mongol

folklore. A line of 360 leather rings run in a line perpendicular to the bowman in the

middle of two rows of dirt mounds. Men shoot at a distance of 75 meters; women from 60

meters. The object is to barely clear the first mound and pierce the targets. A scattering

of red rings bring bonus points.

Lest it sound too easy, Mongolian bows have no sights. Arrows, made of willow sticks and vulture feathers, are tipped with huge hexahedral ends made of roughly-carved bone. The strings are tough, taut bull tendons, that test any champion..

Events, including such modern additions as hurdles and running races, continue non-stop, an entire nomadic Olympics in a weekend. Booths offer meager fare reflective of the widespread shortages gripping Mongolia in the midst of its painful transition to a free market. There are pancakes and breads wrapped around a few gristly chunks of mutton. And after the bottles of Russian soda are exhausted, celebrants share ladles of fermented mare's milk.

If anything, the ancient celebration of Naadam has grown vastly more important in a nation facing rationing of everything from milk and meat, to biscuits, bread, soap and vodka. Unemployment, unknown in the past, has become rampant throughout the nation.

The hard times only underline the precious qualities of Naadam and the Mongols' joy for it. Outside the stadium, barkers advertise handmade games of chance, sometimes only a dimestore dartboard nailed to a tree, or a game wheel consisting of a piece of wire on a board.

"Naadam is everything to us," said Batbulik, a student in Ulan Bator. "After all the years with Russia, everything is gone, the food, the vodka, sometimes it seems, even the fun. But Naadam has been ours forever. Nobody can take Naadam from Mongolia."

Ron Gluckman is an American journalist based in Hong Kong, who travels widely around the Asian region for a variety of publications, including the South China Morning Post, Sydney Morning Herald, Wall Street Journal and Discovery, all of which ran varying versions of this same dispatch from Mongolia in 1992. He has also written about the Naadam for Time, Winds and Far East Traveler.

For a look at the latest Naadam, in July 2003, see Mongolia's Manly Sports.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]