NFL targets China

Every year America's National Football League sponsors college leagues and special events across China, culminating in a kind of Super Bowl, most recently featuring Hall of Famer Joe Montana. Yet unlike basketball, this American export has barely gained any yardage in the world's biggest sporting market.

By Ron Gluckman/Guangzhou, Beijing and Hong Kong, China

HOURS BEFORE KICKOFF, the stands were already packed. The smell of burgers lingered in the air. Cheerleaders cartwheeled on the sidelines, and jubilant fans pounded clack-sticks with gusto.

It was a perfect Super

Bowl Sunday, only the teams weren’t vying for the

National Football

League championship; they were in Guangzhou, China, where civilization

has existed for 5,000 years, but exposure

to football—at least

the U.S. variety—only goes back a decade.

It was a perfect Super

Bowl Sunday, only the teams weren’t vying for the

National Football

League championship; they were in Guangzhou, China, where civilization

has existed for 5,000 years, but exposure

to football—at least

the U.S. variety—only goes back a decade.

Soccer, or European-style football, is beloved here in the world’s most populous nation. Yet American football remains largely unknown. It barely cracks the Top 20 of China’s most popular sports, ranking far below table tennis and badminton, according to CSM Media Research.

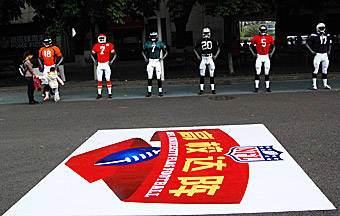

The NFL is trying to change that. Over the past few years, the league has started about a dozen flag and tackle football teams in major cities across the country, where Chinese players and U.S. expats compete and receive equipment, coaching and training.

The NFL has also steadily begun a Chinese promotion campaign that combines general outreach and education with broadcasts and special events. The games I witnessed in Guangzhou, for instance, featured an appearance by Joe Montana, the Hall of Fame quarterback who won four Super Bowls for the San Francisco 49ers.

“I remember soccer in America when I was growing up,” he said. “Hardly anyone played. But now it’s very successful. I think once the Chinese are exposed to [football], they’ll love it too.”

There is some precedent for success. In recent years, basketball has cracked China’s massive market, and today the sport’s international stars appear on giant billboards across this hoops-crazed country. Yet basketball surged in part due to the popularity of Chinese players, and because it’s an Olympic sport, which means government officials have a major incentive to promote it.

Neither is true for football, and

many say the sport will be a tougher sell because of its violent nature. After decades of

strict population

control, which limits most

families to a single child, Chinese

parents, the stereotype goes, often dislike contact sports.

Neither is true for football, and

many say the sport will be a tougher sell because of its violent nature. After decades of

strict population

control, which limits most

families to a single child, Chinese

parents, the stereotype goes, often dislike contact sports.

Richard Young, the head of the NFL’s China office, discounted this assumption. “Our research shows that 9 million Chinese are interested in the NFL, and we classify 3 million as fans,” he said. “That’s more than double than last year. The interest is growing rapidly.”

Maybe, but these numbers are paltry when you consider that China boasts more than 1.3 billion people. Only a tiny fraction of NFL games reach television audiences in China, mainly through highlight clips on sports programs. Unlike basketball, which is widely played and followed by fans of both a professional Chinese league and inter-Asian League, football is only practiced by clubs in a handful of cities—Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu and Guangzhou. Most discover the sport via Internet streams and chat rooms, if they’re ever exposed to it at all.

Football is the most popular sport in the U.S. But the NFL’s record for international expansion isn’t exactly stellar. In 1990, it bankrolled the World League, which evolved into a European football league and eventually folded due to lack of popularity. And though the NFL stages annual games in London, and posts sellout crowds, these are novelty events; actual play remains a niche attraction.

Young, the NFL China executive, discounts the idea that football is too

foreign to catch on in China. Critics, he notes, said the same thing about pizza and Western fast food,

which are now big business here. He may

be right.

Young, the NFL China executive, discounts the idea that football is too

foreign to catch on in China. Critics, he notes, said the same thing about pizza and Western fast food,

which are now big business here. He may

be right.

The NFL estimated that 5,000 people attended Super Bowl Sunday and watched Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine stun Guangzhou Sports University 16-10. Those in attendance seemed impressed. “It’s a great team sport,” said Walter Yeung, age, 23, a Guangzhou resident who discovered football online.

The game was held at Tianhe Sports Center, a modern complex of stadiums built by the city of Guangzhou for the 2010 Asian Games, a regional Olympics of sorts. American football was not represented at those games, nor can you find its footprint in the area. The main stadium features an enormous mall of sports shops. You can buy basketballs, volleyballs, tennis balls, even judo uniforms. There are tennis shoes, soccer cleats, roller skates and kites, but not a single football, let alone a helmet or a pair of shoulder pads.

Even at the Sheraton Hotel across the street, nobody knew anything about the Super Bowl raging nearby. When I asked about the game, a man at the concierge consulted his computer for several minutes, then beaming, wrote down some Chinese characters that directed me to the Tianhe complex and a giant KFC-sponsored demonstration of basketball.

The obstacles facing football’s growth are daunting in China, where sports tend to be run by government offices or sponsored by companies looking for promotional benefits. American-style football, some say, lacks cache for businesses, and won’t produce Olympic medals, a huge lure to promotion-eager officials. “It’s just such a huge market here, it’s really hard to have much impact,” says David Cantalupo, the former head of ESPN’s China division.

Yet the emergence of a Chinese star could be a game changer. When Yao Ming,

the most popular basketball player in Chinese history,

left the Shanghai

Sharks to play for the Houston Rockets in the NBA, his success gave

basketball a serious boost. Today, Chinese

youth mob basketball courts

across the mainland, and their parents spend millions on basketball

paraphernalia each year.

Yet the emergence of a Chinese star could be a game changer. When Yao Ming,

the most popular basketball player in Chinese history,

left the Shanghai

Sharks to play for the Houston Rockets in the NBA, his success gave

basketball a serious boost. Today, Chinese

youth mob basketball courts

across the mainland, and their parents spend millions on basketball

paraphernalia each year.

But the NFL doesn’t expect to see overnight success. Young has set modest goals and hopes to make football a top 10 sport in China within the next decade. Sports consultants credit the league for its long-term approach to building the game. “They are investing in training and building a real grassroots organization,” Cantalupo says.

That’s because the future of football in China will likely depend on new fans like Cena Duan, a 25-year-old who works in marketing for BMW. Six months ago, he saw his first football game online and was instantly hooked. Now he plays quarterback and wide receiver for the Chengdu Mustangs, a team in Central China.

”My friends think I’m crazy,” he says. “They say, ‘Football? In China?’ But when you see it played, you start to understand. This is a man’s sport. If I have a son, he’ll play football.”

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter

who

has been living in and covering Asia since 1991, including 17

years spent in China and Hong Kong, where he struggled endlessly to needle

friends and relatives back home to record sporting events that he'd watch a year

or two later. Then, they invented the internet, and streaming, and it was good.

Ron has covered various American sports in China, including the NBA and MLB.

This story was for Vocativ.com in December 2013.

All words and photos copyright Ron Gluckman

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]