Can't we Chant

Viciously repressed by the communists, Buddhism was almost beaten to death on the reverent steppes of Mongolia, but religion is making a glorious revival amongst the gleeful descendents of Genghis Khan

By Ron Gluckman / Mongolia

B

ELLS WELCOME THE DAWN IN DARHAN. Bazarrachaa sets incense in a brass bowl, then folds his legs as he squats on a carpet and begins a blissful chanting. In Mongolia's capital of Ulan Bator, sweet-smelling smoke engulfs a dozen

stubble-headed children who begin the day by stumbling through Tibetan texts at the

rapidly-expanding Gandan Hiid monastery school.

In Mongolia's capital of Ulan Bator, sweet-smelling smoke engulfs a dozen

stubble-headed children who begin the day by stumbling through Tibetan texts at the

rapidly-expanding Gandan Hiid monastery school.

Three hundred miles away, a bus filled with jabbering tourists braves rutted roads to reach Kara Korum, site of an enormous monastery, the largest in the land. For visitors, monks and devotees alike, the day of devotion represents a new dawn for Buddhism in a homeland where it formerly flourished.

Mongolia is again moving to the ancient hymns and hopes, the echoes of which have been subdued here for decades. Once a center of the Lama brand of Buddhism, this nomadic nation is rediscovering its immense religious heritage after a horrifying series of Soviet-inspired purges.

The exact depth of the repression will never be known, but historians have, in recent years, uncovered numerous mass graves that illuminate the grim fate of thousands of Buddhist monks who vanished in the periodic purges from the 1930s through 1960s.

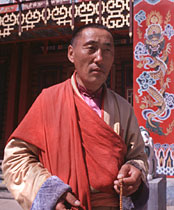

Bazarrachaa is typical of a new wave of Mongolian monks. Five years ago, in the waning days of communism, he was a truck driver. Now, he is leader of the new Buddhist community of Darhan.

Darhan, with a population of just 30,000 people, is nonetheless the third largest city in this sprawling nation of only 2.1 million people and 10 times as many cows, sheep, horses and yaks. Yet they posses a religious zeal that survived seven decades of official antagonism and mass executions. Bazarrachaa says that throughout the turbulent times, Buddhism never died, it merely went underground.

"My father

was a monk. And his father, too. I learned chanting

at home, in secret, like most Mongolians," says Bazarrachaa, proudly fingering his

beads in public, a pleasure that could have cost him his shaved head a few years ago.

"Our home was always Buddhist."

"My father

was a monk. And his father, too. I learned chanting

at home, in secret, like most Mongolians," says Bazarrachaa, proudly fingering his

beads in public, a pleasure that could have cost him his shaved head a few years ago.

"Our home was always Buddhist."

Bazarrachaa says ten monks consecrated Darhan’s first temple in decades. Formerly a school, the temple has been repainted in the Taiwanese-style of bright Buddhist hues of orange, yellow and red. Bazarrachaa says much of the temple material has come from patrons in Taiwan, who have supplied many of the new monasteries around Mongolia. Other support has come from Nepal, Hong Kong and India.

This temple now claims 30 monks and 20 disciples, plus a tremendous community following. "Probably 1,000 people come to pray every day," he says. "Religion is coming again to Mongolia."

Not that it ever went away. Lamaism arrived from Tibet at about the same time as Genghis Kahn, who, in the 13th century transformed the horsemen of these steppes into a fierce fighting force that conquered the largest empire the world has ever known. Three centuries later, the empire shattered, Mongolians retreated to the religion that replaced shamanism when Altan Kahn converted to Buddhism in the 16th century. He sanctioned the Yellow Sect and authorized widespread construction of temples, shrines and monasteries.

The most magnificent of these was Erdene-dzuu, built from the ruins of the great Mongol

capital Genghis' son Ogedi Khan established at Kara Korum. The ancient city rivaled any

then in existance. The palace had silver fountains, with jeweled lion and snake heads,

from which wine, beer and mead poured.

The most magnificent of these was Erdene-dzuu, built from the ruins of the great Mongol

capital Genghis' son Ogedi Khan established at Kara Korum. The ancient city rivaled any

then in existance. The palace had silver fountains, with jeweled lion and snake heads,

from which wine, beer and mead poured.

Long after Kara Korum was razed, monks moved the rocks and rubble to construct a religious complex that was equally impressive. Containing 70 temples and shrines, Erdene-dzuu was ringed by a massive wall, studded with 108 stupas, sepulcher shrines pointing to the heavens. In all, Mongolia once claimed more than 700 temples and 7,000 shrines.

Erdene-dzuu, like other temples scattered across the steppes, was left in shambles by the communist campaign of repression initiated by Stalin and his Mongolian protege, Choibalsang. Only a handful of Buddhist temples were maintained as museums, in much the same manner as Hitler sanctioned the preservation of a sole synagogue in Prague to serve as a monument to his eventual extermination of the Jews of Europe.

In the countryside near Ulan Bator, in an ancient wildlife area that became the world's first national park many centuries ago, are the ruins of another majestic monastery. The photographs in Manjshir museum are painful to view. They show a sprawling community that numbered 10,000 monks and disciples. Livestock grazed peacefully among the gers, traditional Mongolian huts.

Present reality offers only a crude reminder of what was once a spectacular holy site.

A pile of stones high on the sacred Bodg Uul mountain are the only markers of this

Shangri-la; Manjshir was used by Russian tanks for target practice.

Present reality offers only a crude reminder of what was once a spectacular holy site.

A pile of stones high on the sacred Bodg Uul mountain are the only markers of this

Shangri-la; Manjshir was used by Russian tanks for target practice.

Similar signs of destruction can be seen in each of the sprawling Mongolian aimags, or provinces. However, the dark days are over for Mongolia's Buddhists. From the sands of the Gobi desert in the south, to the Hinte mountains in the north, temples are being rebuilt and monasteries restored at a furious pace. "I've been all over the country, in every aimag, and there is at least one temple in every main city, astonishing, since a couple years ago, there were only a handful in all of Mongolia," reported Robert Storey, author of the Lonley Planet guide book to Mongolia.

Indeed, even the smallest cities can claim a religious revival. And Buddhists weren't the only flock to benefit from the new religious freedom. Two Christian churches were holding Sunday services in Ulan Bator. Far north, by the Russian border, the bush village of Moron boasted not only a two-room Buddhist temple, but two Christian evangelists from America.

"Our goal is to bring Jesus to Mongolia, but also to help in any way possible," said Lew Schrader, a Virginia volunteer who arrived in the country in 1990. A church, he says, may be years away in a country where the only record of contact with Christianity came 700 hundred years ago, according to legend, when Genghis Kahn wrote the pope for 200 missionaries. "He sent two, just like us," Schrader said.

Far more prevalent in the countryside are monuments to the ancient Mongol faith that

preceded even Buddhism. Mounds of stones, littered with bones, money and other offerings,

dot every dirt road. Few cars pass without stopping for driver and passengers to add

tributes to the ancient gods.

Far more prevalent in the countryside are monuments to the ancient Mongol faith that

preceded even Buddhism. Mounds of stones, littered with bones, money and other offerings,

dot every dirt road. Few cars pass without stopping for driver and passengers to add

tributes to the ancient gods.

"Shamanism is still prevalent among the population, especially in the countryside," said Zheng Wei, a Chinese movie maker who spent five years documenting shamanism in Inner Mongolia before beginning a similar project in Mongolia in April 1992. Wei says worship of spirits in the hills and forests is ingrained in every aspect of Mongolian life.

"So much of life, from birth rituals and weddings, right down to blessing the horses, is governed by ancient traditions," he said.

Mongolia's shamanistic tradition may explain why Lamaism so quickly took root. The Tibetan religion offers a constantly reincarnated Living Buddha, who can answer prayers in much the manner of the ancient spirits. Mongolia's last living Buddha, Bogd Gegeen Javtsandamba Hutagt, was third in the Lama hierarchy after Tibet's Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama. In the 1920s, Mongolia claimed 110,000 monks, including children - a third of the male population. Yet, even under the communists, 94 percent of Mongols embraced the Lama faith, according to census statistics.

The Mongolian democratic movement gained momentum when the Berlin Wall fell in late 1989. The following year, the country elected its first democratic government and began free market reform. Religion followed with even more severe upheavals.

The national head of Buddhism, a monk called Gaadan, was abruptly banished from Gandan, the only officially-sanctioned religious center under the old government. "He was a communist," hissed a monk at Ulan Bator's Gandan, where 10,000 monks once lived. "He was not a man of religion, but a spy. Now we have religious freedom, and no spies. Our children are finally learning Buddhism in the right way"

Gaadan, now a broken man living in a spare apartment in the capital city, dismisses the charges as rumors spread by rivals. He said his faith never faltered during the difficult years as head monk under the communists from 1980-1990, and it certainly hasn't since his dismissal in the zeal of the democratic movement.

"Socialism had the feeling that Buddhism wasn't necessary for people. That's the basic socialist theory," he said. "The communists closed Gandan for four years and many of the temples were used for storing cars. They were vandalized. But the people still came and prayed secretly. Sometimes the government made us go away. The old government made its rules and the new government makes its own. But, inside the temple, there is a different rule"

Gaadan, now 71, admits concern over the direction of the new Buddhist leaders. "Not everything is real Buddhism. Some monks have not even studied religion," said Gaadan, who, as a boy, studied in a monastery and later mastered Tibetan and Mongolian scriptures, which he taught at the state university. "Some are becoming monks because it's like a business for them, or because of the power. They're using religion.

"Buddhism is different now," he said in voice cracking with emotion. "The old monks follow the old customs, but the new monks are different. They drink vodka and beat people. They don't know chanting. They cannot read the texts. Buddhism will never be the same in Mongolia."

During an overnight ride on rough dirt roads from Ulan Bator, the cows scatter as our car approaches a lush valley along the Selenge River, which drains into magnificent Lake Baykal in Russia. For hours, we have seen herds of horses, but no sign of human settlement. Suddenly, in the faraway green hills, there appears a startling smear of red. Miles further, we stop at the spectacular Armabayasgalant monastery.

This sprawling secretive Shangri-la, built in the 1600s, is the second-oldest and second-largest monastery in Mongolia. However, it's the only religious site to survive intact the communist rule. Pilgrims argue whether the isolated refuge was spared because tanks couldn't travel so far, or razing the religious site wasn't deemed necessary since it served no nearby population center.

In any case, Armabayasgalant is the sleeping giant of Mongolian Buddhism, not even mentioned in tourist brochures or guidebooks. Few Mongols have even heard of it.

Yet, on a summer day, the sound of hammers echoed through the cobwebs as workers pounded new life into the nation's religious treasure. Overseeing the multi-million dollar restoration was Deva Lama Rinpochhe, a Nepalese monk and colleague of the Dalai Lama.

Rinpochhe, who is 86 and blind in one eye, has felt the pain of religious persecution

firsthand. Born in Inner Mongolia, he fled the purges of the Chinese, spending decades in

Tibet and Nepal. Speaking through a translator, he says spirits guided him here "and

I have decided to rebuild this beautiful monastery. We'll use my own money."

Rinpochhe, who is 86 and blind in one eye, has felt the pain of religious persecution

firsthand. Born in Inner Mongolia, he fled the purges of the Chinese, spending decades in

Tibet and Nepal. Speaking through a translator, he says spirits guided him here "and

I have decided to rebuild this beautiful monastery. We'll use my own money."

He said he has no intention of running Armabayasgalant when it reopens in a few years. "I'm too old and have my own temple in Katmandu. But Mongolia is my country. I want to help my people regain their religion."

Rinpochhe, who has a diamond-encrusted Rolex peeking from under his orange robes, said he has already spent US$300,000 on the restoration. Most supplies have been shipped from India, but the brightly-decorated ceiling tiles came from Taiwan. Supporters around Asia have donated other matierl. "The work will be hard, because this is so remote," he said. "But soon, even here, there will be chanting."

There is chanting that night, around a fire, where several cars park in the grassy meadow in front of the monastery. Monks from Gandan and Erdene-dzuu have made their first holy pilgrimage to the remote religious site.

"Restoring the old religion takes time," said Nangid, head monk at Erdene-dzuu. "It's a good thing. During communism, the chanting stopped. Now, the people are free. This is one of the good things of democracy. But it will take time."

He is sharing sips of vodka and airig, the Mongolian national delicacy of fermented mare's milk, with Bayanbat, secretary to the head of Gandan monastery. "It will take many, many years, to bring about a new age of Buddhism in Mongolia," Bayanbat says. "It will take 20 years for real Buddhism to return.

"Mongolia is a big place. Religion, true religion, cannot come quickly. It will take time," he adds, gulping the Mongolian liquor. Then, in the vibrant Mongolian moonlight, he surveys the ancient religious city and smiles. "But we have time. We have time."

Ron Gluckman is an American journalist based in Hong Kong, who travels widely around the Asian region for a variety of publications. He made several trips to Mongolia as it emerged from seven decades of Soviet rule in the early 1990s, reporting for the Toronto Globe and Mail, USA Today, Discovery, Sawasdee, the San Francisco Examiner, Sydney Morning Herald, South China Morning Post, Asia, Inc., and American Express magazines.

This story was done for Good Weekend, the Sunday magazine of the Sydney Morning Herald and Melbourne Age.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]