Kashgar's brilliant bazaar

Miles from nowhere, mid-way between Rome and Beijing, this exotic oasis used to be the last outfitting station on the centuries-old Silk Road. Trade remains timeless still, at least on Sundays, when the entire community gathers at the world's liveliest market.

By Ron Gluckman /Kashgar

A FULL HOUR BEFORE DAYLIGHT, desperate to escape the pre-dawn chill, I dart inside a darkened teahouse, but only for a moment.

Soon, I'm back outside, braving the cold,

drawn by a cascade of animal calls. Eyes wide, hands wrapped for warmth around

my cup, I slip into a corner table outside the teahouse, fearful not to miss a

minute of the morning's magic.

Soon, I'm back outside, braving the cold,

drawn by a cascade of animal calls. Eyes wide, hands wrapped for warmth around

my cup, I slip into a corner table outside the teahouse, fearful not to miss a

minute of the morning's magic.

Sure enough, I've barely settled, cross-legged on a woven mat, before an enormous flock of sheep sweep past, followed by carts laden with cages of birds of every description.

The squawking and clouds of feathers still hover in the air when even better entertainment appears: a pair of elderly, toothless gents prying back the lips of a camel, examining the local transport with all the zeal of potential used car buyers kicking the proverbial tires.

Already the wee hours resound with the arresting aroma of mutton and agitated reverberation of the weekly arguing.

Fridays and Saturdays may be peaceful prayer days in Kashgar, mesmerizing Muslim city at the westernmost frontier of China. Still, Sundays are nearly as sacred in this Middle Eastern-flavored crossroads that is much closer to Pakistan, India and Iran than Beijing.

Sundays, you

see, are market days. Just

not the buy-it and bag-it variety. Shopping, like practically everything in

Kashgar, is an ancient art form in which no transaction transpires quickly.

Sundays, you

see, are market days. Just

not the buy-it and bag-it variety. Shopping, like practically everything in

Kashgar, is an ancient art form in which no transaction transpires quickly.

Haggling is spirited and can consume an entire day. And involve the entire community, which religiously gathers every week, along with thousands of visitors, for the famed Sunday market, Xingiri Shichang in Chinese, but better known as Yekshenba Bazaar to local Uighurs.

Hence, after tea-break, I'm dodging sheep as I slither around multi-story stacks of socks, scissors and shawls. And vats of fluorescent-hued spices and carts overflowing with the frisbee-sized flat-breads that are, to Kashgar, what rice is to the rest of China.

From fluffy sheepskin hats to rugged camel-hide boots, not to mention beads, buttons and buckets of local lard, everything - including plenty of kitchen sinks - is for sale at ths fairytale bazaar, a veritable Market At the End of Earth abounding with more special effects than George Lucas could dream up.

And more than mere

marketplace, Kashgar's amazing bazaar is an anything-goes civic center where you

can have your hair cut, watch a boxing exhibition, even test-drive a donkey or

horse.

And more than mere

marketplace, Kashgar's amazing bazaar is an anything-goes civic center where you

can have your hair cut, watch a boxing exhibition, even test-drive a donkey or

horse.

For centuries it has been so at this desert oasis, a last-chance outfitting station along the fabled Silk Road, mankind's first superhighway, connecting the world's two great empires, Rome and China, two thousand years ago.

Back then, camel caravans laden with Chinese silk, spice and porcelain, would stagger into Kashgar after the perilous crossing of the Taklamakan Desert - whose name says it all. The nearest translation: Those Going In Never Return.

Yet it was hardly smooth sailing further westward, with more than 4,000 rugged meters to ascend through treacherous mountain passes on the trail to India or Pakistan, and the hungry European markets beyond.

No wonder many weary traders lingered in this last bastion of civilization. Some stayed, opened shops, prospered and carved a marvelous metropolis from sand and rock.

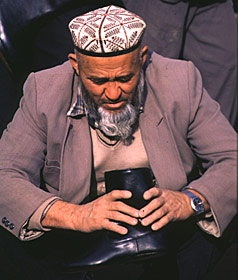

Just as much as the stunning scenery - desert dunes roll right to the base of snow-capped mountains - it's the people of the region who give Kashgar its color.

Tribes from nearby mountain villages - Tajiks, Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, Uzbeks - long ago blended with Arab traders, Russian adventurers and Hun warriors in a melting pot that bubbled over a Wild West boomtown too distant for the dictates of faraway emperors.

Early settlers were hearty as well as industrious. They built one of the world's

oldest irrigation systems, funneling glacial melt from distant mountains to

desert, turning sand into a land of milk and honey.

Early settlers were hearty as well as industrious. They built one of the world's

oldest irrigation systems, funneling glacial melt from distant mountains to

desert, turning sand into a land of milk and honey.

All the teeming produce in Kashgar today - raisins, grapes, figs and almonds - result from those ancient waterworks (or karez). Some are 2,000 years old, but can still be seen feeding fertile fields outside Kashgar, where one can actually can stand with one leg in barren sand and the other in vineyards.

Contrast and continuity are the constants of this rugged land, buffeted by sandstorms and some of the world's wildest temperature variations. In sizzling desert summers, the thermometer soars over 40 degrees, dipping in winter to minus 20-25 Celsius.

Equally dramatic extremes extend to the terrain as well. The Taklamakan claims the world's second lowest point; it's shadowed by some of the world's highest mountains.

Then, there are the intriguing contrasts of the main square, a good starting point for any tour of Kashgar. Mellon vendors and bike repairmen frequent the square by day, but every night it hosts a fascinating collection of food stalls.

Amidst intoxicating smells of cumin and pepper, mutton is grilled, boiled and

deep-fried in huge vats of oil, along with a mouth-watering array of meats,

river fish and vegetables. And mounds of fresh-baked breads - or nang; there are

more than four dozen local varieties.

Amidst intoxicating smells of cumin and pepper, mutton is grilled, boiled and

deep-fried in huge vats of oil, along with a mouth-watering array of meats,

river fish and vegetables. And mounds of fresh-baked breads - or nang; there are

more than four dozen local varieties.

A satisfying supper can be had for $1-2. But food is simply a starter at this market. Each night, the square changes its offerings like a revolving-door bazaar.

One night, the theme is electronics, with piles of old televisions, radios and other odd bits of metal, wrapped in spaghetti wire. The next night might be devoted to footwear, with house-sized piles of shoes, surrounded by booths selling socks, laces and nylons.

Above the square, a large clock tower keeps the time. Herein lies another of Kashgar's delightful contradictions. The time is never right, nor can it be.

The enormous distance from Beijing means that Kashgar should be two to three time zones behind the capital. However, national law keeps all clocks ticking to the same hour. For several thousand years, though, Kashgar has made its own rules, and time is no exception. Locals simply set clocks back two hours.

Hence,

visitors often arrive at locked shops, even though it's 10 a.m. - officially,

anyway. It can provide a shock, like when I roll into Caravan Café and find

morning coffee actually starts at 1 p.m. "It takes some getting used

to," chuckles co-owner Greg Kopan, "but everything is in a different

zone here."

Hence,

visitors often arrive at locked shops, even though it's 10 a.m. - officially,

anyway. It can provide a shock, like when I roll into Caravan Café and find

morning coffee actually starts at 1 p.m. "It takes some getting used

to," chuckles co-owner Greg Kopan, "but everything is in a different

zone here."

And how. Travel writers like to talk about timeless places, but Kashgar is the genuine article.

Ancient dirt paths - often barely two-donkeys wide - spin around the old city in a marvelous maze embracing biblical-era mud-brick houses. Every corner seems to sprout an old mosque, and neighborhoods reverberate with the haunting call to prayer.

Yet Kashgar is a relaxed place, where some women are covered in Muslim headdress, even as others favor colorful fashions. The men tend to sport big furry hats with bushy Abraham Lincoln beards, adding to the intriguing look of a city like no other in China.

Perhaps that's why purists shuddered a few years back as train tracks skirted the Taklamakan desert, connecting Urumqi to this westernmost outpost. The fear was that modern commodities would pour into Kashgar along with passengers, thereby yanking this ancient land into the present.

Much the same worries

circulated years previously as planes began landing in Kashgar at the urging of

upscale Silk Road tourists without the stomach for a monstrous trek that had

been upgraded over the centuri es from camel to bus, but remained almost as

uncomfortable.

es from camel to bus, but remained almost as

uncomfortable.

All the fears have proven largely unfounded. Reaching Kashgar nowadays is a breeze, but the fabric of the city still seems cut from a cloth all its own.

Oh, there have been changes. Take haggling, for instance. In olden times, two robed men might negotiate the price of a sheep secretly, without a sound. Exchanging greetings, they would grasp hands and, hidden beneath their long sleeves, settle on a price by wiggling their fingers back and forth.

These days, nothing, especially bargaining, is done quietly - or quickly - in Kashgar. But in the teahouses and squares, the timeless bazaar continues unabated.

The clock tower may be off by a mere two hours, but Kashgar still ticks to its own rhythm, tucked in a mysterious Central Asian time warp that hasn't changed in centuries.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has spent over a dozen years in Greater China, roaming the region for a wide variety of international publications. This story appeared in the January 2003 issue of Morning Calm, the Korean Airlines magazine.

All pictures by Ron Gluckman, except top photo of Ron Gluckman taking tea with some of the locals, which is by Frederic La Grange.

For more on Kashgar and see Ron's dispatches from the Silk Road: Another Cultural Revolution and Strangers in their Own Land.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]