Going Offline in Asia

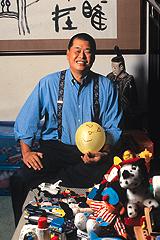

Hong Kong entrepreneur Jimmy Lai had an idea that could have redefined shopping in the world's department store. Instead, his bold e-commerce venture sucked up $130 million of his money, and sent the media magnate reeling to Taiwan. AdMart could have been the next big e-thing, instead of another dotcom doom story.

By Ron Gluckman/Hong Kong and Beijing

I

F ANYONE SHOULD HAVE KNOWN how to deliver online shopping to Hong Kong it would have been thought to be Jimmy Lai, a local multimillionaire who always seemed to have an uncanny knack for knowing what the public wanted. So it looked like doomsday for the local e-tail sector when, on Dec. 10, 2000, he closed the doors on his online grocery-shopping business, AdMart. As it turned out, AdMart offers a case study in how smart ideas don't always sail in Asia's often-frustrating new economy. Lai's

rags-to-riches rise is well known in the region: He fled China alone as a child

and worked his way up from textile factory floors in Hong Kong to found his own

clothing chain, Giordano. Many liken it to Asia's version of The Gap.

Lai's

rags-to-riches rise is well known in the region: He fled China alone as a child

and worked his way up from textile factory floors in Hong Kong to found his own

clothing chain, Giordano. Many liken it to Asia's version of The Gap.

Known for his almost religious belief in freedom and democracy, Lai then turned to publishing -- a risky bet since there were already roughly 50 newspapers in the former British colony in the mid-1990s when Lai launched his oddly named Apple Daily. But Hong Kong developed an appetite for the often sensationalist and sometimes outspoken paper, which quickly become the second-best-selling Chinese language newspaper.

Lai wasn't an early convert to the internet. "I don't even know how to check my email," he once confided to this reporter. Still, when Lai saw something he liked - whether a boat, a deal or a newspaper niche - he jumped in head first. Once he caught net-fever in early 1999, he began gushing about the possibilities.

"It's changing the world, business, politics, the way we shop, the way we live," said Lai of the internet, when he announced the launch of his online grocery-shopping site AdMart.com in June 1999. "Whenever I think of the Internet, my adrenaline rushes."

Modeled after American Internet grocery service Webvan, AdMart seemed even better suited to Hong Kong, a dense metropolis of nearly 7 million work-aholics with scant leisure time. Besides, only 14 percent of Hong Kong households claim cars. Add in the fact that US grocery prices are kept low by intense competition; grocery shopping in Hong Kong, by contrast, is dominated by two chains that divide some of the world's highest supermarket margins.

Enter Lai, with a fleet of brightly-painted vans and a flood of advertising in his paper. The other grocery chains had web sites, but they were slow, limited in scope and costly to use. AdMart offered spiffy service and unheard-of prices. Cans of soda, 60 cents elsewhere, were home-delivered for 20 cents. AdMart offered quick deliver at no charge.

As the competing chains frantically cut prices and matched the free delivery, agile AdMart added electronics, housewares and computer equipment.

Yet in 18 months the company lost more than $130 million. In late October, 100 employees were cut from various Lai online operations as his publishing company shut down a dozen sites. In December, the company's demise resulted in a loss of 344 jobs -- the largest single layoff of the year in Hong Kong's gloomy new-economy sector. Other dot-coms in the city shed some 1,000 Internet jobs during 2000.

"AdMart is more problem than I ever imagined," Lai admits now. Analysts in the region, meanwhile, point out that minor differences between the Hong Kong and US consumer markets proved to be critical.

While Americans have been willing to take advantage of Webvan's delivery and buy in bulk, living space in Hong Kong is so cramped that few people have the cupboard space needed for bulk buying. Also, food shopping is an experience deeply ingrained in the Chinese culture of Hong Kong, where a maid -- or, in working-class families, a wife who also holds down a job -- is likely to visit the market twice a day so that both lunch and dinner will be made from the freshest ingredients. People like to feel the food, touch it, squeeze it.

Yet other e-tail ventures have also failed across Asia, which many hoped could be the new Net frontier. Forrester Research predicts that online spending in Asia should reach $1.6 trillion by 2004, second only to North America. And by all measures, Hong Kong should lead the fray within Asia.

Internet penetration is gauged at 46 percent in Hong Kong, according to the 2000 American Express Global Internet Survey. That beats Japan (27 percent) and even the United Kingdom (35 percent).

Lai is planning to turn back to his old media empire and expand into Taiwan, where the democratically elected government also sets his pulse racing.

Chief executives determined to stick with dot-coms, though, have begun to give up on Hong Kong and take the route so many old-economy companies have: China. (Former British colony Hong Kong is now part of China, but it is a so-called Special Administrative Region with a separate -- albeit Beijing-appointed -- government and a genuinely autonomous economic system.)

There's no comparison, after all, between a half-saturated market of 7 million and a potential market of 1.4 billion Internet users.

While China's usage currently is little more than 1 percent of the population, it doubles every four to six months. "A lot of these things are a matter of timing," insists Patrick Horgan, director of telecoms/IT at the Beijing office of the consultant firm APCO.

Granted, China is no place for those who lack the capital and patience to hang in for the long term, making it difficult for a fledgling business. Take the case of Zou Jun. The 30-year-old Beijinger left a promising career with the local accounting office of KPMG to help launch an online book vendor called Jingqi.com.

"China has room for 10 Amazon.coms," he boasted at the outset. Even without the hype of Amazon, books seemed to be a safe bet in China, which has a voracious reading audience. Over $10 billion was spent last year on books, according to Zou.

Yet selling them online proved to be another matter. Distribution channels in China are primitive. Credit cards have only recently been introduced. Zou recounts how his company devised innovative cash-on-delivery schemes through backdoor deals with the postal system, and used a fleet of bike messengers for delivery.

After a few months, however, Zou gave up the company and moved to a consulting firm. But he remains sold on the Net. He says the key is finding the right model, and believes Jingqi was a good idea whose time hadn't come.

The same could be said about AdMart and scores of other Asian dot.coms. As Horgan puts it: "There's no cultural reason that e-commerce won't work here."

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who is based in Hong Kong, but who roams around Asia for a wide variety of publications, including many new media, like tnbt(the-next-big-thing).com which ran this piece in January 2001.

Pictures is courtesy of Ira Chaplain

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]