Bikeman's endless adventure

For 40 years, Heinz Stucke has circled the globe by bicycle. Along the way, he's been shot at, robbed, arrested, and celebrated, embraced and admired in every corner of the planet. But Stucke rarely sticks around for the accolades. He's a timeless wanderer. The Bikeman just keeps rolling.

By Ron Gluckman /Mongolia, Beijing and Hong Kong

F

OR DAYS, WE HAD BEEN STUCK IN ULAAN BAATAR, capital of Mongolia, scheming, dreaming of some way out. Ironically, slipping in had seemed the big challenge. This was over a decade ago, when the first cracks in the Iron Curtain left just enough room for a few plucky westerners to skirt the strict Russian-style controls on tourism.Still, euphoria reigned that summer of 1991. Across the steppes, nomads flocked into Ulaanbaatar to celebrate the first free Naadam, the ancient Olympics started by Genghis Kahn, after seven decades of Soviet repression. Celebrations ended in chaos as this new nation blew its entire fuel supply at independence parties. Trains and trucks stalled. Food was in short supply.

Hence, our dilemma. Mongolia isn't an easy place to tour in the best of times; we're talking the world's southernmost permafrost and northernmost desert. Finally, some friends hired a bus, buying precious petrol coupons on the black market. Bouncing into the tundra, we felt like absolute pioneers. Until I glanced back on the road and saw the real thing: a stout westerner astride a bike, muscular thighs pumping, conquering the world's most rugged terrain, a few inches at a time.

That was my first sight of the living legend, Heinz Stucke, possibly the world's most traveled man. For four decades now, he's relentlessly ridden the same cycle through rain, sun, chaos or coups. Later the same day, after we'd reached the countryside, he rolled into our camp of gers, round, felt-like Mongolian huts. We swarmed around the fire, pressing for tales of his great adventures. Then, as now, Stucke simply shrugs off the attention. "There's nothing extreme about me," he says. "I just ride a bike."

Yet nobody living has ridden longer or farther. At 1.65 meters, he's a compact 70 kilos. With thinning hair and ruddy complexion, he hardly looks hardcore. That's the great thing about Stucke, the understated record-setter. He's circled the globe 10 times, and he's done it the old fashioned way, with sheer will power. Even now, in his 60s, Stucke sticks to the road on the same clunky old three-speed cycle, eschewing special gear and high-tech alloys. His pace is monitored by no team vans. His story is one steeped in personal accomplishment. And stamina.

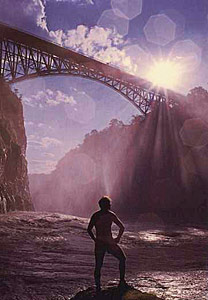

Stucke has nearly died of thirst on a reckless crossing of the African desert,

and been stung into a stupor by swarms of bees in Gambia. He's been shot by

rebels in Zambia and swept up in civil wars from Algeria to Vietnam. A lifetime

of tales are tucked into a pile of notepads he packs in his saddlebags. A

meticulous organizer - "I can tell you exactly what I was carrying - five

years ago," he tells me sternly one day as we bake in the radiant Mongolian

sun - Stucke has an encyclopedic memory for all the places he's been in a tour

that makes Gulliver's Travels seem like kids stuff.

Stucke has nearly died of thirst on a reckless crossing of the African desert,

and been stung into a stupor by swarms of bees in Gambia. He's been shot by

rebels in Zambia and swept up in civil wars from Algeria to Vietnam. A lifetime

of tales are tucked into a pile of notepads he packs in his saddlebags. A

meticulous organizer - "I can tell you exactly what I was carrying - five

years ago," he tells me sternly one day as we bake in the radiant Mongolian

sun - Stucke has an encyclopedic memory for all the places he's been in a tour

that makes Gulliver's Travels seem like kids stuff.

Some of these tales he tells that summer in Mongolia, when we travel briefly together. Others are elicited over the ensuing decade in a variety of settings: beers in Hong Kong, by phone from a hotel in Paris or, most recently, in the southern United States, where Stucke abruptly emerged after riding practically every inch of Cuba.

Keeping in touch with this manic vagabond has never been easy, since Stucke has no fixed address. He's never had a phone or fax. Or paid tax. Despite being a potential poster guru for hotmail, he abhors email. "It's like an addiction," he explains with typical stubbornness. "It's just another thing that eats into my time."

Little else has. Stucke was 18 when he began his first big bike tour, solo four and a half months around Europe in 1958. Adventurous for a teen, it was simply a training-wheel tour for the Bikeman. Within two years, he was back on bike, pedaling 17,000 kilometers through 20 countries. Mark that down as the trip-of-the lifetime for a lesser man. A year later, Stucke hit the road again. Forever.

"I realized, why work your life to save up to retire, when I could spend my life traveling," says Stucke. Even so, bidding family farewell, he had no idea he would never see his mother again, nor return to his native Germany. The year was 1962 and The Beatles were just hitting the charts. John F. Kennedy was in the White House, and Oliver Stone, like much of America, hadn't even heard of Vietnam.

It was an innocent time, for Stucke, too. He wasn't thinking of setting records. His only plan was to cycle forth and see the world. He just never stopped.

From Germany, he cycled southwest. Crossing from Spain to Morocco, he

rode south through Africa for two years, until land ran out. Along the way came

a stream of eye-opening adventures, far beyond the imagination of this one-time

machinist's apprentice from Hovelhof, population 10,000. Among the highlights:

meeting Ethiopian Emperor Haile Salassie.

From Germany, he cycled southwest. Crossing from Spain to Morocco, he

rode south through Africa for two years, until land ran out. Along the way came

a stream of eye-opening adventures, far beyond the imagination of this one-time

machinist's apprentice from Hovelhof, population 10,000. Among the highlights:

meeting Ethiopian Emperor Haile Salassie.

"A story on my trip appeared in a local paper, and I was invited to parliament," he recalls. "One of the ministers arranged the meeting." Young Stucke was infused with a sense that anything was possible; he retains a never-say-no attitude. He also gained something concrete - a gift of US$500 from the Emperor. For Stucke, who left Germany with $300 and had been subsisting on 50 cents per day, this was a fortune. In the Cape, he boarded a freighter to South America. The Emperor paid his passage.

After arriving in Rio in early 1964, Stucke's pace slowed. He moved in meandering circles, whims of the road and chance encounters dictating his destination. Now, he was a true hobo, only on two wheels. "I never really thought of myself as a biker," he says. "In the beginning it just happened to be the cheapest way to travel."

Stucke spent four years in Latin America, adding Spanish to his languages. He speaks good English and can get by in a wide variety of other tongues, including Arabic and Japanese.

The following three years he toured North America, covering more ground than NAFTA. From Mexico, he followed the Gulf coast to New York, retreated to Florida, then went north to Canada and to America's most distant point, Alaska's North Slope. He did it all by bike, until winter iced the Yukon Highway.

Stucke accepted a ride from fellow travelers who totaled the car that night. His bike was trashed. As usual, he didn't dwell on the downturn. Stucke simply continued by road to Alaska, returning later for his bike, which he patched together as best as possible.

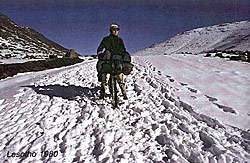

That bike is almost as legendary as Stucke himself. Lycra-clad racers

leave sneering notes on bike web sites about the clunker that was a gift from a

German company. Stucke acknowledges that it seems more suited to the Smithsonian

than ascents of the Andes; yet he's taken it over a Himalayan pass at 5,360

meters.

That bike is almost as legendary as Stucke himself. Lycra-clad racers

leave sneering notes on bike web sites about the clunker that was a gift from a

German company. Stucke acknowledges that it seems more suited to the Smithsonian

than ascents of the Andes; yet he's taken it over a Himalayan pass at 5,360

meters.

"The bike weighs a good 25 kilos," admits Stucke. Blame thick spokes and heavy luggage racks on a reinforced frame. "Sure, I could use something lighter, but why?" Stucke is attached to his only companion, this old 26-inch wheeled cycle with pedal brakes. Stolen several times, in San Francisco, Columbia, Turkey and the Philippines, it's always been returned, miraculously, following appeals to the police and public.

Bike and rider stand out on any road. Saddle bags draped around the frame bulge with upwards of 25 kilos of gear. Sometimes 55 kilos. "I know, it's crazy, that's what everyone says." And gear? Nothing conventional like dehydrated food for this traveler, whose typical chow is a Stucke stew - basically anything handy tossed in a pot.

He's more finicky about camera equipment: he carries heavy Nikon and big tripod. Decades ago, Stucke began shipping slides to a London agent, who sold stories from the journey, raising a few thousand dollars each year, which kept the Bikeman rolling through his early years..

"We hear from him now and then when he needs money," says Mike Soulsby, director of Frank Spooner Pictures, which has fielded Stucke's slides for a quarter of a century. Much of the time, payments have been more a kindness than actual reimbursement for sales, Soulsby says. Owner and founder Frank Spooner, now in his late 80s, admits: "I've felt some responsibility for him over the years. He'd ring up, usually in some sort of crisis and I'd always send money, whatever I could."

Others have been similarly moved. For many years, Stucke supported himself with sales of booklets about his trip. The idea arose in 1971 in Japan, where Stucke earned $20,000, which kept him rolling for six years. He's never matched that success, but still pauses for periodic reprints. He's a lousy capitalist, though, pricing the booklets to local conditions, often for pocket change, or giving them away. But the bike gypsy knows the wiles of the road. Friendships strike up and invitations result from the street sales.

His fans are intensely loyal. "He's amazing, one of the most remarkable people I've ever met," says James Stroud, 39, who met Stucke in the mid-1980s in Africa. Stroud was on a 16-month trip with his girlfriend, now his wife. "We had joined one of those truck trips, which was the only way to get around Africa, which was pretty near impossible in those days." Stucke, of course, was on his bike. And he had his sights set on Chad, then was closed and in the midst of civil war.

"I'd heard about him before, this remarkable character who had already been riding around the world for 25 years at the time. When I met him, the amazing thing was how normal he seemed. I mean, here's this guy who has done this absolutely unbelievable, unrealistic thing, and he's just a regular guy."

Stucke drops by Stroud's house in London periodically, always

unannounced, always welcome. He's godfather to one of Stroud's five children.

"Heinz is different. He's not like the other record seekers. There's a

natural quality to him. A purity. That's what makes him what he is, which is a

true great traveler."

Stucke drops by Stroud's house in London periodically, always

unannounced, always welcome. He's godfather to one of Stroud's five children.

"Heinz is different. He's not like the other record seekers. There's a

natural quality to him. A purity. That's what makes him what he is, which is a

true great traveler."

Indeed, Stucke's travels touches a free spirit in us all. He's been a frequent guest at the Kirby house in Anniston, Alabama, where he landed last year after his roll around Cuba. On hand was Chris Kirby, a baby when Stucke first pedelled into the family's life in 1968. "Heinz has inspired all of our family in many different ways. For me, I pursued photography," says Chris admiringly. "He has taught me how to appreciate life through imagery."

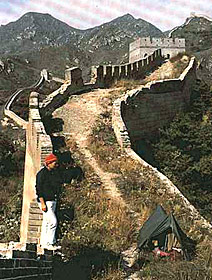

Others talk adoringly about the Don Quixote-like qualities of Stucke's travels, but fret over his future. "I respect him for what he's doing, not that I'd want to do that myself," says Andre de Smit, an entrepreneur in China who sees Stucke whenever the Bikeman rolls through Beijing or Hong Kong. "He's a colorful character, but take away his bike, his travels, and what does he have? What worries me, I guess, is where he is going. I mean, he's getting old now and more concerned about money."

Clearly, Stucke has grown less carefree. "I'm getting old, I'm feeling it," he confided a few years ago in Hong Kong. The talk rapidly turned to other downers, like loneliness on the road. "How can I have a girlfriend? It would slow me down. I must remain free, able to ride where I want, when I want."

Much has changed since our first meeting in Mongolia. While waiting for a visa for Russia on that trip, Stucke found out that the USSR had splintered into pieces. His reaction could only be described as glee. "That just means that many more countries left for me!" Stucke quickly crossed Siberia, which remains one of his favorite stretches. "In the beginning, I wanted to meet people, see cities. Now, I just like being alone on the road. Give me 1,000 kilometers of Bush, and I'm happy.

"People always ask, what do you do when you are riding? Aren't you bored? But I never am. I have a vivid imagination, and there is always so much to see and think about."

Besides long stretches of thought-provoking emptiness, the former USSR delivered another surprise to Stucke - romance. In 1992, he met Zoya, a single mother in Belarus. The two have maintained a relationship that is fittingly unconventional. "We see each other two or three times a year," Stucke says. "Sometimes she joins me on trips."

Never on two wheels, though. "She's never learned to ride a bike," he says. "She's scared of bikes! Can you believe that?" Instead, Zoya hitches ahead to a prearranged spot, and they rendezvous every night. Romance on the road, Bikeman style.

Yet the relationship has had some influence on Stucke. Or perhaps it's age. In any case, he's talking about settling down. Maybe writing that great bike book. "I often think of Heinz and think he's been wasted," says Spooner. "There seems such a good book in him. I mean, he left home in 1962 as a young man. Now it's the end of the century. To me it always seemed such a crazy thing, but he was so intent, and now he's finished. All that is left is to tell the story."

Certainly, there is ample interest, now that Stucke has completely conquered the world. After tackling the new nations born of Russia's demise, he ticked off the final few from his list: Albania, Angola and the tiny African island republics of Sao Tome and Principe. Last was the Seychelles in 1996.

But six years on - and 40 years after he kicked up the bike-stand on

one of the world's great travel adventures - there has still been no

celebration. "All I could think of was all the places and territories I

have never been," Stucke says, "like Greenland, Antarctica and the

Galapagos. And the places that I only visited shortly." Cuba was among

them. Stucke went during his first tour of the Americas in the 1960s.

"Then, it was a closed place and I couldn't take my bike," he says. On

this last trip, he logged 2,360 kilometers.

But six years on - and 40 years after he kicked up the bike-stand on

one of the world's great travel adventures - there has still been no

celebration. "All I could think of was all the places and territories I

have never been," Stucke says, "like Greenland, Antarctica and the

Galapagos. And the places that I only visited shortly." Cuba was among

them. Stucke went during his first tour of the Americas in the 1960s.

"Then, it was a closed place and I couldn't take my bike," he says. On

this last trip, he logged 2,360 kilometers.

At 62, this cyclist shows no sign of putting down the kickstand. In 2000 alone, he says, he rode 18,360 kilometers. "That made it the second-best year in cycled distance in 38 years," he says. "I'm proud of that."

In Stucke's mind, there is really only one finish line. "In the end," he says, "there will be a gateway, and over it a sign. The sign will say cemetery. That's the end for everyone." Then, he hops back on his bike, just a bit less gainfully than that first time we met, all those years ago in Mongolia. "Riding is all I want to do," he insists."People are surprised, after all these years, but I like it better now than in the beginning."

Then, off he goes again, Heinz Stucke, one of life's last rugged individualists, taking the world entirely on his own terms, one turn of the wheel at a time. For Stucke, the future is an endless road. His last words: "I'll ride till I'm dead."

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has been based in Beijing and Hong Kong since 1991, roaming around Asia for numerous publications including several that have run his stories about Stucke, including the Wall Street Journal, Winds, the South China Morning Post and the Toronto Globe and Mail. You can see one example of those shorter stories at Bikeman's Amazing Adventure.

Continuing interest in the exploits of this amazing bikeman prompted me to spend over a year tracking him down and talking with him for this piece, which was commissioned by National Geographic Adventurer.

For the complete story of this amazing adventure, look at http://www.bikechina.com/heinzstucke1z.html, an excellent site run by Peter Snow Cao, another cycling enthusiast who arranges trips in China and the region. The story posted by Peter is from Stucke's own booklet, which includes a nice selection of pictures of Stucke's trip (more like those here, borrowed from the same booklet). I have my own photos of Stucke buried somewhere in my files, but, unfortunately, am not as efficient a archivist as Stucke himself. I promise to find and post them sometime...

In the meantime, wherever you happen to be, keep an eye peeled on the distant roads. Somewhere out there, Stucke is still riding.

To Heinz - long may you ride!

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]