China's artistic bloom

A photo festival in Beijing, in partnership with the world's oldest photography festival in Arles, France, is said to signal the emergence of China and its ambitious artists as part of a new genre of photography. Yet the sunny gathering at Caochangdi was missing its most famous resident - artist Ai Weiwei. It's another reminder that you cannot have an artistic awakening without freedom.

By Ron Gluckman/Beijing, China

A

DESOLATE DISTRICT OF BRICK WAREHOUSES

The event, which runs through May 31, is organized by some of Beijing's

top art galleries in partnership with the world's oldest photography festival in

Arles, France. Photospring not only promotes emerging Chinese photographers, but

showcases some of the world's most celebrated ones. This year marks the second

installment of the festival, which debuted in spring 2010.

The event, which runs through May 31, is organized by some of Beijing's

top art galleries in partnership with the world's oldest photography festival in

Arles, France. Photospring not only promotes emerging Chinese photographers, but

showcases some of the world's most celebrated ones. This year marks the second

installment of the festival, which debuted in spring 2010.

Hosted by Three Shadows and a dozen other galleries, all located at Caochangdi or the nearby 798 arts districts north of Beijing, the event's broad offerings tackle topics rarely discussed in China—at least in public. Blind justice is unveiled in "The Innocents," U.S.-based Taryn Simon's evocative portraits of wrongfully convicted people. In one, Tim Durham is portrayed on a shooting trip; eleven witnesses placed him at such an outing, but he was jailed for rape and robbery, serving three and a half years of a 3,220-year sentence.

It's not only foreign photographers who address society-rattling subjects. Many Chinese photographers poignantly depict themes that include mass urbanization, evictions and environmental degradation. He Chongyue focuses his lens upon China's controversial family-planning policy.

Equally arresting are intensely personal displays, like that of Zhe Chen,

who snaps her self-inflicted wounds. "Disturbing, but undeniably beautiful,"

comments one onlooker. Ms. Zhe won the Three Shadows Photography Award and a

80,000 yuan ($12,200) prize.

Equally arresting are intensely personal displays, like that of Zhe Chen,

who snaps her self-inflicted wounds. "Disturbing, but undeniably beautiful,"

comments one onlooker. Ms. Zhe won the Three Shadows Photography Award and a

80,000 yuan ($12,200) prize.

"What we see here, is Chinese photography inventing itself," says Francois Hebel, director of Les Rencontres D'Arles Photographie, as the prominent French festival is known. "We see an entirely new school of photography developing, like in no other country in the world."

"It's really the invention of a whole new genre," he adds enthusiastically. "It's something we haven't seen in the West, at least not in a long time. It's all happening here before your eyes, bursting out right in front of you."

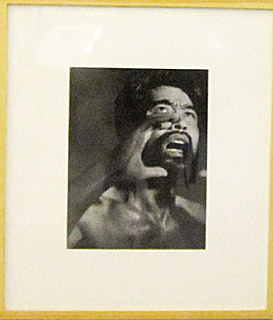

Yet, parts of the event are grounded in history or lineage. Perhaps the most stunning exhibit is Chinese, but with a wonderful twist. "Reappearance" offers a look at the first international exhibit of modern Chinese photographers, in 1988 in Arles. Showing it in China brings full circle nearly a quarter century of difficult international artistic cooperation.

Many images look hopelessly dated, in starkest black and white. We see

camels coming through old city walls, soldiers working fields, and other clichés

of the Cultural Revolution and closed-door era. Still, the stilted portraits of

Mao and other Communist Party icons serve as a wonderful reminder of the

struggle of the old generation of Chinese photographers.

Many images look hopelessly dated, in starkest black and white. We see

camels coming through old city walls, soldiers working fields, and other clichés

of the Cultural Revolution and closed-door era. Still, the stilted portraits of

Mao and other Communist Party icons serve as a wonderful reminder of the

struggle of the old generation of Chinese photographers.

Some critics think modern mainland artists have it easy. Fueled by newly affluent Chinese collectors and international buyers, Chinese art prices have boomed; China photography has ridden the same wave. Ms. Zhe accepted her award hours after flying from Southern California, where she attends Pasadena's Arts Center College of Design. "I didn't even pick up a camera until a few years ago," she admits. Many pictures in her mesmerizing project were shot on a cell phone.

"To live in China and be a photographer is easy," adds Taca Zhijie Sui, another promising young artist originally from Qingdao, Shandong province, at Photospring. "It's easy to sell, and there are so many projects to do," says the artist, who divides his time between China and New York. "In New York, it's not as easy."

Photospring also offers a chance to view internationally renowned work, and attend lectures, seminars and symposiums. "We're after substance," explains Bérénice Angremy, an art curator and director of the festival. "In the first year, the challenge was just to pull it off. Now, we want it to evolve, mature."

The organizers made efforts to increase interaction among those who attend the festival, with emphasis placed on bringing more curators and gallery owners to China. One key symposium deals with collecting. "We want to help build up a larger artistic community," she says.

One member of the Caochangdi community missing at the opening is

Ai Weiwei. China's best-known artist was taken

into custody April 3, and has not been seen since. A prominent photographer, he

is also one of the architects who designed Three Shadows, and many of the

district's galleries.

One member of the Caochangdi community missing at the opening is

Ai Weiwei. China's best-known artist was taken

into custody April 3, and has not been seen since. A prominent photographer, he

is also one of the architects who designed Three Shadows, and many of the

district's galleries.

While Photospring may signal a blossoming for part of Beijing, Mr. Ai's detention casts a black cloud over the festival, and China's artistic aspirations. Oddly, no mention of Caochangdi's pioneer is made at the opening, and no petitions or banners demanding his release are on view. "Naturally, we are all concerned," says one organizer, a friend of the detained artist, "but there isn't much we can do. We'd be shut down."

Nearby, the residence of the artist who helped build Caochangdi sits deserted; gone are the secret police who lurked outside for months. Instead, kites flutter in the April sun, which reflects brightly on a sign on the gate of Mr. Ai's home.

A ferocious critic of China's pell-mell development and accompanying corruption, Mr. Ai's courageous, confrontational approach—even when he's absent—continues to speak volumes about the ugly side of China's advance. The sign on the gate denotes the name of his art and architecture firm, but also resonates with his message: "Fake."

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has been living in and covering Asia since 1991. He covered the opening of Photospring 2011 in late April 2011, which is when this piece ran in the Wall Street Journal.

Ai Weiwei remains missing, believed to be in detention in China.

Note: In early April, on the way to Hong Kong, Ai Weiwei was taken away by Chinese authorities, and has remained in detention in an undisclosed location ever since. We extend our fondest hopes for his good health and safety, and urge you to support organizations calling for the release of Ai Weiwei.

All pictures by RON GLUCKMAN, except the framed print, from the exhibit of Chinese photographers in the 1980s.

Words and pictures, copyright Ron Gluckman

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]