After the Olympics

Whether Beijing's 2008 Olympics can be considered the best, or greenest ever, remains to be decided. But one thing is sure, the legacy of this Olympics won't be White Elephant stadiums. Unlike Olympics of the past, plagued by overspending and waste, Beijing did its best to ensure that this will be one Olympics earning a gold in civic planning.

By Ron Gluckman/in Beijing

STAGING AN OLYMPICS involves more energy and preparation than any marathon. Long years of planning are generally followed by a few months of manic construction in the final sprint, leading to a finish line of near-total panic.

Then, for two or three weeks, amidst the

bright glow of television spotlights, the world celebrates not only the finest

athletes from around the globe, but also the acumen and architecture of the host

nation.

Then, for two or three weeks, amidst the

bright glow of television spotlights, the world celebrates not only the finest

athletes from around the globe, but also the acumen and architecture of the host

nation.

If all goes well, after the medals are awarded, the blood tests scrutinized, and the bags packed, the lights go out once again for another four years. And the host nation, along with all the fine facilities it designed and built at great expense especially for the Olympics, instantly become yesterday’s news.

That’s the typical scenery for any Olympics. And whatever letdown athletes or competing nations might suffer, the roller coaster between global fame and being forgotten is especially severe when it comes to Olympics facilities. Many are custom-built for specific Olympics events, and in the rush to get ready, scant thought is usually given to subsequent use. Hence, as much as the tradition of the Olympics is brotherhood amidst friendly competition, the legacy for the facilities has too often been boondoggles and white elephants.

No big stadium built for an Olympics has ever really proved profitable, and many become huge burdens on host nations, with maintenance fees often crippling civic budgets for years to come.

Perhaps the best – or worst - example comes from Montreal, whose Olympics stadium would have been by far the most expensive ever built. Originally budgeted at $128 million, it never fully opened and was scrapped at a cost of $1.4 billion. Locals refer to it as the Big Mistake.

Sadly, such mistakes continue to repeat themselves. Montreal’s Olympics was over three decades ago, and the record since has been nearly as dim. Athens, birthplace of the Olympics in 776 BC, constructed a score of spanking new facilities for the 2004 games. Nearly all remain unused only four years later.

Over-spending and under-utilization has long been a footnote to the grandeur of

the Olympics, but Beijing set about to break the mold by learning from the past,

and planning well in advance. While spending by China in 2008 was by far the

most ever showered upon an Olympics – an estimated $42 billion, or about 10

times the Athens expenditure – Beijing looks certain to break even on nearly

every one of its Olympic arenas.

Over-spending and under-utilization has long been a footnote to the grandeur of

the Olympics, but Beijing set about to break the mold by learning from the past,

and planning well in advance. While spending by China in 2008 was by far the

most ever showered upon an Olympics – an estimated $42 billion, or about 10

times the Athens expenditure – Beijing looks certain to break even on nearly

every one of its Olympic arenas.

How it achieved this astounding efficiency isn’t all due to astute planning. Beijing offered a rare urban landscape. Much spending was on big-ticket items like an expansion of the subway system, improvements that were needed even if the Olympics had not been held in China. Other funds bankrolled various environmental measures, as Beijing strove to host the greenest Olympics ever.

By most yardsticks, Beijing reached or exceeded its ecological goals as neatly as it launched a new era of more efficient Olympics facilities.

Nearly $2 billion was spent to

build 12 permanent and eight temporary venues for the Olympics. Some of these

facilities were even more overdue than the subway expansion, guaranteeing that

they would remain in use long afterwards.

With a population of about 15 million, metropolitan Beijing depended on its old Worker’s Stadium to serve big events, like Asian football (or soccer). The 40,000-seat stadium, a throwback to the Soviet alliance of the 1950s, is cramped and lacks modern boxes, but it was the biggest and best Beijing had to offer.

Hence, plenty of pent-up demand greeted the construction of the Bird’s Nest, as the exquisitely designed new National Stadium from Herzog & De Meuron Architekten AG has been dubbed. Chinese sports clubs and civic groups are lining up to book the state-of-the art 91,000-seat stadium.

That iconic facility has become world famous, but practically all other Olympics stadiums have been well received and fill immediate needs in Beijing. Many were built alongside existing universities, where they are already becoming integrated into campus facilities. The wrestling venue will become a 6,000-seat gymnasium for the China Agricultural University, while the 6,900 seat badminton gym was turned over to Beijing University of Technology.

In coastal Qingdao, the Olympics boating facilities will be converted into a

public marina and government school for sailors.

In coastal Qingdao, the Olympics boating facilities will be converted into a

public marina and government school for sailors.

Such smooth transitions should not minimize the extent of Beijing’s pre-Olympics planning. Practically from the day China won its bid in 2001, the government set about to ensure that its Olympics legacy was unique.

The best example is probably the press center and broadcasting building, which not only served 21,000 journalists, but also hosted fencing and shooting events. That was during the Olympics. Now, it starts its new life as the China National Convention Centre, with some of the top exhibition facilities in the country. With the addition of hotels and shopping, it will become a trendy new tourist and business center in the Chinese capital.

Actually, this was the plan for the facility from the outset, according to Ross Milne, director of the Hong Kong office of international architecture firm RMJM Hillier. “From the start, the focus of the developer was the site after the Olympics,” says Milne, who explains that the design was for a multi-faceted convention center, with supporting hotels and retail. “Think of it as being really an exhibition center; the Olympics just happened to be the first tenant.”

Milne describes a dual-train design process, which created a bit of extra work. “There was the constant juggling with two different layouts, the post-Olympics design and the Olympics drawings,” he says. There was also extensive scrutiny from both the owner and the Olympics committee, each with different goals in mind. “It was an intense process,” he concedes.

Yet the outcome was not only a high-profile debut, in which the building’s long

glass façade and stunning views over the Olympic greens featured in numerous

broadcasts, but also a speedy transition to post-Olympics life. And the design

yielded considerable savings, too. “The fit-out costs for this were miniscule

compared to what will be gained,” he says. “The entire process really turned the

entire thinking inside out.”

Yet the outcome was not only a high-profile debut, in which the building’s long

glass façade and stunning views over the Olympic greens featured in numerous

broadcasts, but also a speedy transition to post-Olympics life. And the design

yielded considerable savings, too. “The fit-out costs for this were miniscule

compared to what will be gained,” he says. “The entire process really turned the

entire thinking inside out.”

The Olympics basketball arena didn’t benefit from quite the same sort of fast break, but also had a chance to refit for post-Olympic life well in advance of 2008. Construction was already underway on Beijing Olympic Basketball Arena when Beijing Wukesong Culture & Sports Center took over, and signed a landmark pact with the Chinese operations of the American NBA (the National Basketball Association) and leading sports promotion firm, AEG.

Basketball, which has been played in China for over a century, got a huge boost when players like Yao Ming, China’s biggest celebrity, made the transition to the American league. The NBA had been operating in China for decades, offering clinics, merchandise and the odd exhibition games. Together with AEG, they now plan a quantum leap, with the goal of running professional leagues in China.

Key to the plan is a series of high-quality arenas that can offer American showmanship, and generate American-style profits. While China has had many different basketball leagues in the past, few have managed profits, and most teams struggle to break even, playing in high school gymnasium-level arenas.

AEG, the NBA and their Chinese

partner aim to take basketball to a new level, utilizing the former Olympics

arena as the centerpiece of a new NBA-sponsored league, and other high-profile

events, including music concerts. “The Beijing Olympic Basketball Arena will

instantly become the region’s finest and most modern showcase for basketball and

other sports in addition to the most popular performers in the music industry,”

promises Timothy Leiweke, President and CEO of AEG. The firm owns or controls a

number of stadiums in the US, and has interests in franchises in several sports

including ice hockey and soccer.

AEG, the NBA and their Chinese

partner aim to take basketball to a new level, utilizing the former Olympics

arena as the centerpiece of a new NBA-sponsored league, and other high-profile

events, including music concerts. “The Beijing Olympic Basketball Arena will

instantly become the region’s finest and most modern showcase for basketball and

other sports in addition to the most popular performers in the music industry,”

promises Timothy Leiweke, President and CEO of AEG. The firm owns or controls a

number of stadiums in the US, and has interests in franchises in several sports

including ice hockey and soccer.

Construction on the arena began several years before Wukesong took over. With its new partners on board, they launched an ongoing refit and redesign even before 2008. Kansas architect David Manica was brought in to begin tweaking the facility towards its high-profile future.

Working with HOK Sport, a Kansas City firm that designed Toyota Center, home of NBA’s Houston Rockets, Manica began reshaping the arena, inside and out. Originally designed to feature an all-glass exterior, it was switched to undulating ribbons of perforated aluminum. Beijing was pleased with the resemblance to a forest of bamboo, while the designers realized considerable savings in overall weight. Dropping cumbersome supporting columns allowed them to create the shells that would serve future concession stands, crucial to stadium profitability.

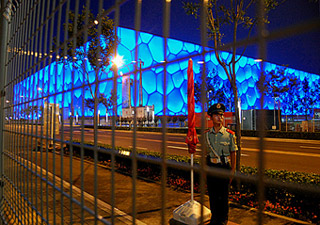

Other savings were registered across the board as Olympics facilities endeavored

to achieve energy efficiencies under Beijing’s goal of hosting the greenest

Olympics ever. The evocative Water Cube, as the National Aquatics Center was

dubbed, features an unique exterior of thousands of plastic bubbles. These

perform miracles of insulation, using natural sunlight to heat the pool,

reducing energy needs by 30 percent - about as much as if the entire roof was

covered in photovoltaic cells.

Other savings were registered across the board as Olympics facilities endeavored

to achieve energy efficiencies under Beijing’s goal of hosting the greenest

Olympics ever. The evocative Water Cube, as the National Aquatics Center was

dubbed, features an unique exterior of thousands of plastic bubbles. These

perform miracles of insulation, using natural sunlight to heat the pool,

reducing energy needs by 30 percent - about as much as if the entire roof was

covered in photovoltaic cells.

The Water Cube also collects and recycles rain water, as do many Olympics facilities. Milne says the Convention Center roof harvests enough rainwater for irrigation and flushing. Solar panels in the Bird’s Nest generate enough energy to power lights for the underground parking lot.

Another factor in Beijing’s Olympic success was the level of coordination and unity over seven years of planning and construction. Engineering firm Arup was behind practically all the Olympic facilities. That helped them tie all the facilities together with an underground road system that not only sped transportation and emergency access, but allowed for coordination of parking, reducing the need for spaces in individual arenas.

Finally, Beijing utilized every means to raise money to finance its Olympics spending spree. Naming rights for the National Stadium will cover much of the maintenance cost, in effect subsidizing the use by local sports clubs. The Water Cube successfully licensed its brand to a bottled water company.

Perhaps the best example of confluence between making facilities pay for

themselves and realize green savings comes at the athlete’s village. Housing for

16,000 athletes was designed from the start as luxury apartments, complete with

the kinds of services – from restaurants to laundry – that are rare in Beijing.

As a result, all the apartments sold out well ahead of the Olympics, at prices

ranging from $3000-$4500 per square meter, high even in the booming Beijing

market.

Perhaps the best example of confluence between making facilities pay for

themselves and realize green savings comes at the athlete’s village. Housing for

16,000 athletes was designed from the start as luxury apartments, complete with

the kinds of services – from restaurants to laundry – that are rare in Beijing.

As a result, all the apartments sold out well ahead of the Olympics, at prices

ranging from $3000-$4500 per square meter, high even in the booming Beijing

market.

Weeks in the staging, but nearly a decade in the planning, the legacy of these Olympic Games is likely to be far more long lasting than the TV images. China not only excelled on the tracks and in the stadiums, but showed with the right attention to detail behind the scenes, a grand Olympics can also be green and pay dividends for the host community for years to come.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has been roaming around Asia since 1991, much of that time based in Beijing or Hong Kong. He was in Beijing in the run up to the Olympics in 2008, when he researched this story for Urban Land Institute.

All pictures by Ron Gluckman

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]